McGill Carriage House Reimagined

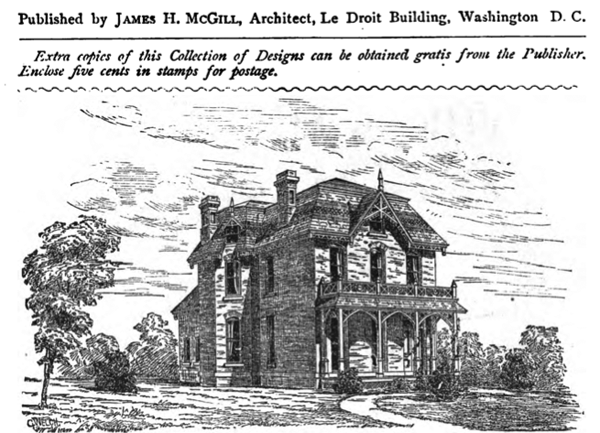

In the last round of concept changes for 1922 Third Street, the developer proposed restoring an old wall (pictured above) attached to the carriage house. The developer added it after we discovered an 1880 architectural pattern book produced by James McGill, the architect of LeDroit Park’s original and eclectic houses.

Google, in its effort to scan and publish old, public-domain documents, scanned the pattern book and posted it online. You will notice engravings of several other houses that still stand in LeDroit Park today.

We have recreated a 3D model of the carriage house based on James McGill’s original design. We had to guess the colors since the McGill publication was printed as a simple black-and-white engraving. Download the Google SketchUp file (get SketchUp for free to view it) or watch the video tour below.

Unlike today’s garages, these carriage houses were designed to house a carriage or two, several horses, and bales of hay. Modern cars, once fondly called “horseless carriages”, obviate need for these equine accouterments and the developer wishes to convert the carriage house into living quarters.

The problem is that the zoning code is more accepting of car housing than of people housing; converting an old carriage house into living quarters will require a zoning variance. Whatever gets built at the site, be it through this developer or another, would ideally include the restoration of the carriage house and its adaptation from housing for horses into housing for people.

* * *

The design for 1922 Third Street will go before the Historic Preservation Review Board on Thursday. Interested parties may comment on the proposal either way at the hearing.

Historic Preservation Review Board – Thursday, April 22 at 10 am at One Judiciary Square (441 Fourth Street NW), Room 220 South. Read the public notice

LeDroit Park in 1921

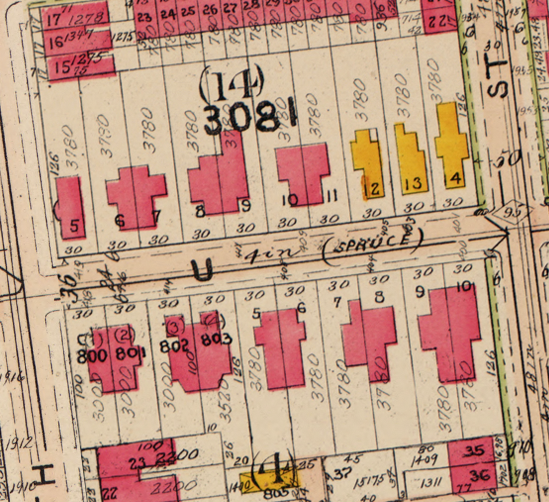

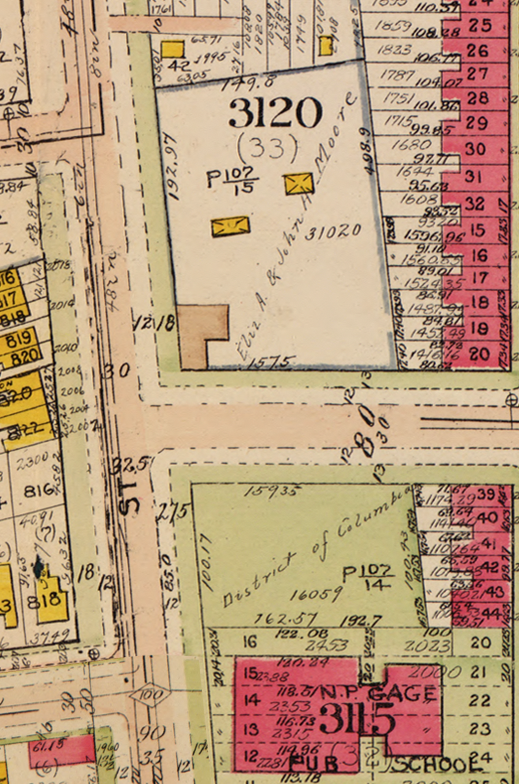

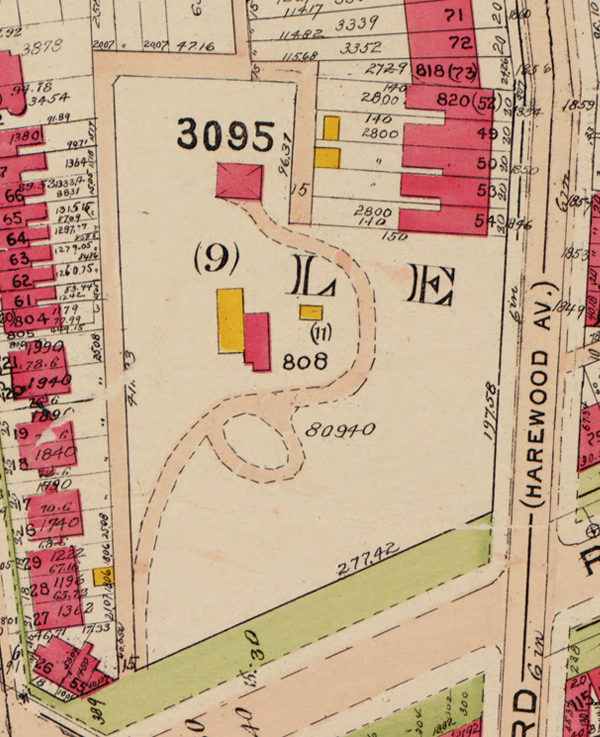

We were paging through the excellent online map collection of the Library of Congress and downloaded the 1921 Baist Real Estate Atlas of Washington, DC. This meticulous city atlas marked all the water mains, sewers, streets, squares, lots, and buildings. Buildings were shaded to indicate their construction materials (red for brick, yellow for wood). Subdivision names as well as the names of certain proprietors made their ways into the Baist maps, too.

We’re actually studying this atlas to do some research for an upcoming post on the zoning code, but for your convenience we’ve stitched together the three pages of the atlas covering LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale and published it as a single PDF document. Here are a few highlights.

The 400 block of U Street, famous for its houses designed by Washington architect James McGill, reveals that the lots 12, 13, and 14 in square 3081 are wood houses, while all the other McGill houses on the block are brick.

Here’s the original Gage School, now a condo building, on Second Street. Notice the Moore property, which predates the establishment of LeDroit Park, extending all the way south to Florida Avenue.

The current site of the United Planning Organization on Rhode Island Avenue was the estate of engraver David McClelland. As we wrote before, the U.S. War Department confiscated Mr. McClelland’s map of the District at the outbreak of the Civil War. The Elks later purchased the McClelland estate and eventually sold it and moved into their current building on Third Street (marked as Harewood Avenue below).

In the 1970s, the city razed all the area shaded in green below to make way for Gage-Eckington Elementary School, which was itself razed just last year after years of declining enrollment.

Carless in LeDroit

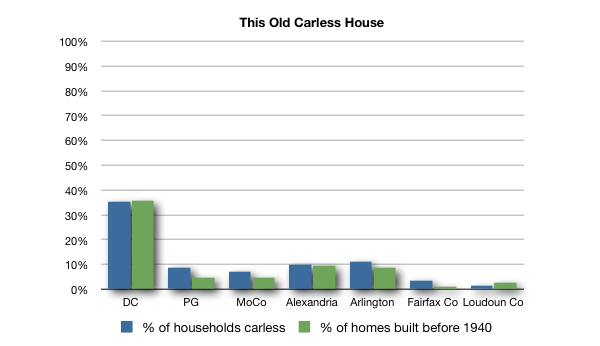

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Among the nicest features of LeDroit Park are its walkability and its proximity to downtown. We can bike downtown to work in 15 minutes, or if it’s raining, take the bus or the metro and be there in 25 minutes. The restaurants, shops, and bars along U Street are only a short walk away.

The notion that it is easy to live in LeDroit Park without a car consistently confounds many suburbanites, but our variety of transportation options is no accident.

Our neighborhood is just outside the original L’Enfant city. In L’Enfant’s time, the main form of transportation was the human foot, so a city designed from scratch, like Washington, had to be relatively flat, like Washington, and compact, like Washington. Horse-drawn streetcars made commuting across the city easier, and electric streetcars eased the daily climb to neighborhoods like Columbia Heights and Mount Pleasant.

After World War II, housing construction exploded, particularly suburban housing construction. The suburban housing model was— and, for the most part, still is— based on several main principles, most significantly, the uniformity of housing sizes (usually large) and the separation of residential and commercial uses. Both larger lots and the separation of uses create longer distances between any two points, requiring a greater effort to go between home, work, and the grocery store.

These longer distances between daily destinations made walking impractical and the lower population densities made public transit financially unsustainable. The only solution was the private automobile, which, coincidentally, benefited from massive government subsidies in the form of highway building and a subsidized oil infrastructure and industry.

LeDroit Park was founded in 1873 and the first wave of single-family and duplex houses designed by James McGill soon followed. The second housing wave brought rowhouses to LeDroit Park, but most of the neighborhood was finished in the early twentieth century long before the dominance of the automobile.

Notice this 1908 photo of the 400 block of U Street in LeDroit Park. You’ll see four people, but only one car.

It’s no coincidence that our neighborhood’s founding, long before the automobile age, relates to its walkability and abundance of transit options. In fact, when we look at the regional Census data, we find a strong relationship between the age of the housing stock and the rate of households without a car.

The only other factor that might influence the rate of carlessness is income, but the closeness of the carless rate and the pre-war housing stock rate is too glaring to ignore. There are plenty of middle-class people in Washington who choose to forgo a private car and the age of the neighborhood may be a strong indication of just how easy it is to live without a car.

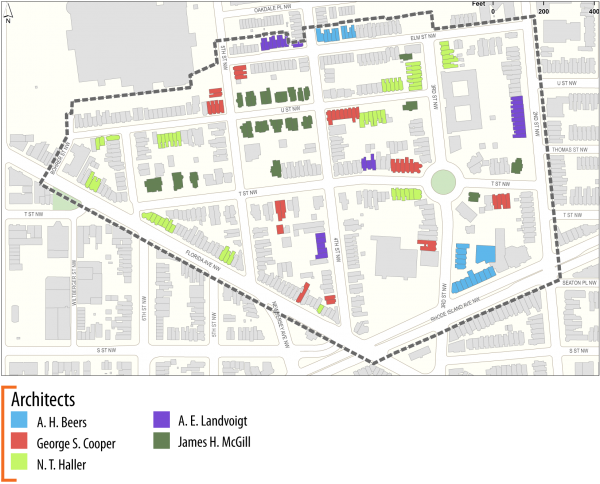

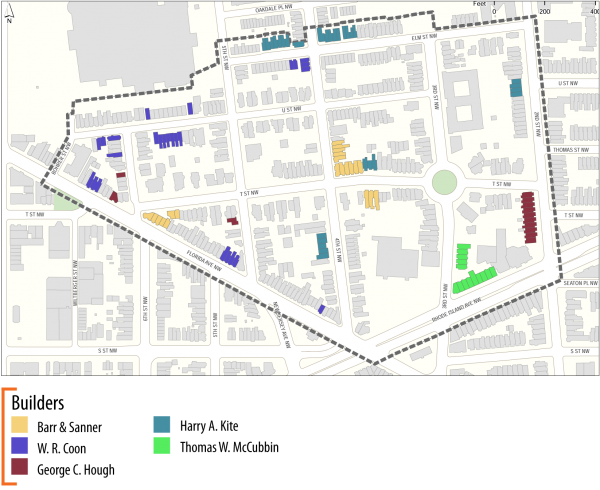

New maps chart LeDroit Park’s architects and development history

The Historic Preservation Office’s newly released 2016 Historic Preservation Plan has some good maps about LeDroit Park’s historic architecture and development.

Architects

Though James H. McGill designed the neighborhood’s original eclectic country houses, architects A. H. Beers, George S. Cooper, N. T. Haller, and A. E. Landvoight designed much of the neighborhood’s subsequent housing. (Click any of the following maps for larger versions)

Builders

If you research your house’s original building permit at the Washingtoniana Division of the MLK Library, you will find that it lists both an architect and a builder. The builder typically hired the architect and arranged for the financing and sale or lease of the finished product. The McGill-designed houses were built by A. L. Barber & Co., but other builders included Barr & Sanner, W. R. Coon, George C. Hough, Harry A. Kite, and Thomas W. McCubbin.

Contributing Structures

Not every building in a historic district is historic or worthy of preservation. The National Park Service defines a contributing structure as one that “by location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association adds to the district’s sense of time and place, and historical development.” A non-contributing building can include “one where the location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association have been so altered or have so deteriorated that the overall integrity of the building has been irretrievably lost.” Also, buildings built within the past 50 years are typically considered non-contributing. (The “50-year Rule” is a common, if controversial, historic designation threshold.)

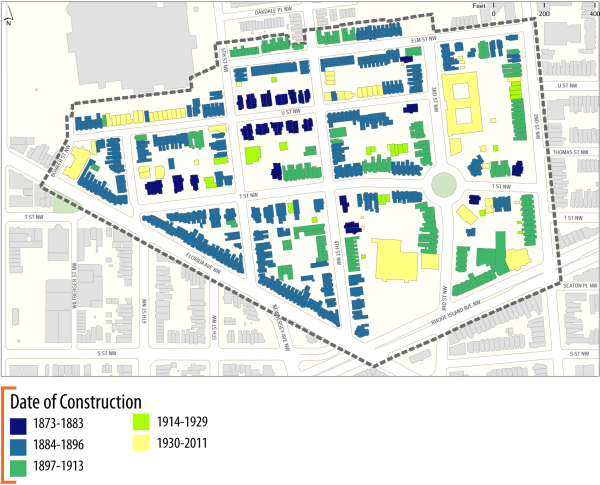

Date of Construction

The McGill houses were built between 1873 and 1883. After that other lots were sold off and developed as rowhouses. Some McGill houses were torn down and replaced with smaller rowhouses.

All of the above maps are from page 69 of the Historic Preservation Office’s report.

Article recounts the early days and residents of LeDroit Park

A Bloomingdale resident share this 1937 news story in which the author recounts the early days and residents of LeDroit Park.

The writer describes what LeDroit Park looked like before 1875, which is about the time the neighborhood started to develop. He recalls that he could stand at 7th Street and Florida Avenue (née Boundary Street) and see all the way down to North Capitol Street.

Few houses stood on Florida Avenue at that time, he notes. The Washington & Georgetown Railroad, a streetcar company, kept a car barn on the triangular block opposite what is now the Howard Theatre.

The neighborhood was created by combining the Miller, Prather, McClelland, and Gilman properties pictured below. The Prather property was used as a pasture and the Miller property was not maintained.

The wood and iron fence, which caused a great dispute in the 1880s, extended from the neighborhood’s boundary at 2nd Street to within a few feet of 7th Street. “At the west of the grounds is an attractive old gate, made to match the artistic fence. It was evidently driveway gate, though its use as such has been abandoned and the driveway itself obliterated.”

Early residents

The author lists several of the neighborhood’s earlier residents. Before LeDroit Park became the favorite enclave of Washington’s black elite, it housed many prominent whites. While few of the people listed below are household names today, many of them held high positions in government.

- Henry Gannett, Chief Geographer, U.S. Geological Survey, and described as the “Father of Government Mapmaking“

- Rep. Benjamin Butterworth, House of Representatives (R-OH) and Commissioner of Patents

- Arthur A. Birney, U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia

- Col. O. H. Irish, Chief, Bureau of Engraving and Printing

- Sumner I. Kimball, General Superintendent, U.S. Life Saving Service, forerunner to the U.S. Coast Guard

- William T. Hornaday, Chief Taxidermist, U.S. National Museum (now called the Smithsonian) and controversial director of the Bronx Zoo

- Arnold B. Johnson, Chief Clerk, U.S. Lighthouse Board

- Edmund Wood, Chief of the Financial Division, Bureau of Indian Affairs

- De Lancey Gill, painter and photographer, Smithsonian Bureau of American Ethnology

- George S. Prindle, patent attorney

- Ellery C. Ford, lawyer (This name appears at the African-American Civil War Memorial on U Street)

- Andrew Langdon, co-developer of LeDroit Park

- James H. McGill, architect of LeDroit Park and other Washington buildings

- Staughton S. Doyle, music teacher

- Ezra B. Barnum, clothier and grand juror who indicted Charles Guiteau, who assassinated Pres. James Garfield in 1881

- Dr. Joseph N. Rose, botanist

- J. J. Albright, possibly the wealthy coal magnate and associate of LeDroit Park developer Amzi Barber.

- Capt. Howard L. Prince, Civil War captain and Librarian of the U.S. Patent Office

- George E. Sloat, employee of the Pension Office

- Charles Ruoff, partner, Willet & Ruoff

- Marie Ginesi, employee of the Post Office

- Charles Darwin (no, not that Charles Darwin), librarian, U.S. Geological Survey

- W. Scott Smith, correspondent, New York Times

Here are names I haven’t been able to research:

Brenton L. Baldwin, Emma B. Smith, F. H. Ramey, W. E. Williams, Ralph Baldwin, B. Pettingill, S. S. Gannett, F. J. Young, Henry A. Merrick, Rev. C. H. Fay, N. M. Brush, Charles W. Fisher, Abram L. Swartout, W. Norman Fleming, Charles A. Hamilton, O.B. Brown, William H. Degges, W. F. Hildebrand, James A. Marter, T. B. Campbell, T. J. W. Robertson, E. M. Merrick, H. B. Wyman, M. Horstman, A. W. Conlee, C. R. Follin, Mary Ragan, Oscar T. Towner, E. Woodruff, W. Hollingsworth, H. E. Cooper, and J. B. Thomas.

If you dig up any information on these people, please add it to the comments.

“LE DROIT PARK. What Three Years Have Done.”

We came across this 1876 article documenting the initial improvements to the nascent LeDroit Park.

LE DROIT PARK. What Three Years Have Done.

National Republican

September 4, 1876Mr. James H. McGill, architect, has forwarded to the inspector of buildings, Mr. Thos. M. Plowman, a communication, in which he furnishes interesting information in relation to the improvements made in LeDroit Park within the last two years. He states that the different tracts of land composing the park were purchased at different times from June, 1872, to March, 1873, by Messrs. A.L. Barber & Co., and united by these gentlemen into one tract, which has been carefully surveyed and recorded. This park is in the form of an equilateral triangle, with one side resting on Boundary street [now Florida Avenue] and reaching from Seventh street eastward to Second street, and contains fifty acres. Until its subdivision by the present proprietor the eastern tract had been used for private residences and grounds, and the western portion had laid uninclosed for several years, and had been used as a public common. Improvements were soon commenced on a liberal scale; a handsome pattern of combination wood and iron fence was adopted and built all along the entire front and a board fence all along the rear, making one inclosure. All the interior fences were removed, and the lots thrown in together, affording a continuous sward. Streets were graded, graveled and guttered, brick sidewalks were put down, and gas, water and sewer mains laid.

The erection of buildings was commenced in July, 1873, since which time eight large brick residences have been erected on the north side of Maple avenue [now T Street] and two on the south side, costing from $4,000 to $12,000 each; ten houses on the north side and ten on the south side of Spruce street [now U Street], at an average cost of $3,500; two houses on the north side of Elm street, costing $3,000 each; four houses on east side, and five on the west side of Harewood avenue [now 3rd Street],costing from $4,000 to $10,000 each. A very superior stable and carriage-house has been completed for A. Langdon, esq., and another is in course of erection for A. R. Appleton, esq. Up to this date forty-one superior residences and two handsome stables have been constructed, at a cost of about $200,000. These houses are either built separately or in couples; are nearly all of brick; of varied designs, no two being alike either in size, shape or style of finish, or in the color of exterior. About $4,000 has been expended in the purchase and planting of ornamental shade trees and hedges, and about $50,000 in street improvements. About 4,500 lineal feet of streets have been graded and graveled, 9,000 feet of stone and brick gutters laid, 5,000 feet of brick pavement, 4,000 feet of sewer mains, 3,550 feet of water mains and 3,800 feet of gas mains laid. All of this expense has been by the proprietors of the property without a dollar from the District or authorities, and all the work has been done in the best and most liberal manner, under the direction of Mr. McGill. The plan contemplates the finishing of all its streets and the erection of two hundred tastefully-designed, conveniently-arranged and well-built detached and semi-detached residences, and when completed cannot fail of being a credit to all concerned. During the time stated the value of improvements constructed in other portions of the county amount to upwards of $100,000.

How LeDroit Park Came to be Added to the City

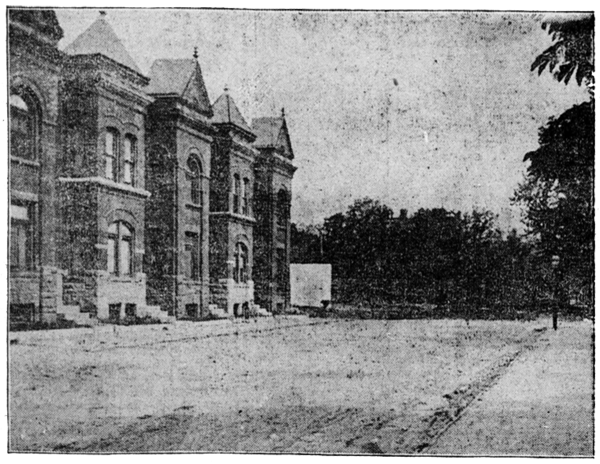

The following is a Washington Times article from 1903. The article explains some of the early history of the neighborhood and even includes three photos, the first of which was misidentified as Fifth Street, though we have actually matched it up with Second Street. We have included a few links to related information.

Second Street opposite the Anna J. Cooper House.

HOW LE DROIT PARK CAME TO BE ADDED TO THE CITY

Washington Times

Sunday, May 31, 1903For Many Years the Section of Washington Known by That Name Had Practically Its Separate Government and Had All the Characteristics of a Country Town, Although Plainly Within the Boundary Limits. * * *

In that portion of Florida Avenue between Seventh Street and Eighth Streets northwest where the street cars of the Seventh Street line and the Ninth Street line pass over the same tracks, thousands of passengers are carried every day, and probably but a few if any realize the fact that they are passing over a road older than the organization of the city, a road that dates back to the Revolutionary period— the Bladensburg Road, which connected Georgetown with Bladensburg before the location of the National Capital was determined.

The Map on the Wall.

If the people passing this point will note the little frame building occupied by a florist, 713 Florida Avenue northwest, they will observe that in front of these premises and fastened to the blacksmith shop adjoining is a goodly sized signboard on which is painted an old map of this section and showing the intersection of the old Blandensburg Road and Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue. From this map it is seen that Seventh Street Road [now Georgia Avenue] intersects Boundary Street and the old Bladensburg Road at a point about 100 feet east of where the two roads join at an acute angle, and glancing along the lines of Boundary Street and the north lines of some buildings which have been erected in this angle we easily see the direction of the Bladensburg Road and discover that the small building 713 Florida Avenue northwest marks the spot where the Bladensburg Road deflected from Boundary Street and bore off in a northeasterly direction toward Bladensburg.

Once Part of Jamaica Vacancy.

The map referred to is said to be a portion of [the estate named] Jamaica and and Smith’s Vacancy, but if we examine the plats in the office of the Surveyor of the District we will hardly find on file any plats of those sections, but may learn that Le Droit Park was once part of Jamaica and Smith’s Vacancy and possibly a portion of [the estate named] Port Royal. Prior to the cession of the territory now included in the District from Maryland the land known as Jamaica was owned by one Philip R. Fendall, of Virginia. He conveyed this tract of 494 acres on the 12th day of January, 1792, to Samuel Blodgett, jr., of Massachusetts, and from this point the title of the land can be traced down to the present time.

The names attached to the different vacancies establish the names of the various owners of lands adjoining Bladensburg Road at the time it was abandoned as a thoroughfare and taken up as a portion of the farms in that section, and the presence of this old road accounts for some of the peculiar lines in some of the northern boundaries of some of the lots in Le Droit Park. This road crossed Second Street at a point north of Elm Street here. The old plats show Moore’s Vacancy. The road finally joined the present road to Bladensburg at a point where the sixth milestone of the norther line of the District was located.

It is probable that this peculiarly natural boundary of some of the lands which afterward became Le Droit Park may have had something to do with the strange lines which are found in the streets of that suburb, although it was not the intention at the time that Le Droit Park was subdivided to have the streets conform with the city streets.

Site of Campbell Hospital.

During the civil war the territory now contained in Le Droit Park was used as the site of Campbell General Hospital, one of the important hospitals near Washington. The hospital comprised some seventeen separate wooden buildings, erected in the form of a hollow square, with the central portion divided into irregular spaces by buildings cutting across the inclosure and connecting the outside buildings.

The larger dimension of this hospital was fro north to south, and extended from Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue, on the south, to the land occupied for many years as a baseball park, situated south of Freedman’s Hospital, and designated on some of the old maps as Levi Park. From east to west the hospital covered the ground from Seventh Street to what is now known as Fifth Street in Le Droit Park, and it is possible that a portion of the space between Fifth Street and Fourth Street was also included in the hospital inclosure.

The McClelland Residence.

At this time there were only two dwellings in the tract known afterward as Le Droit Park— the McClelland and Gilman homestands. Each included about ten acres of land used for grazing and garden purposes. The McClelland property and the Gilman property were divided by a row of large oak trees which were situated about fifty feet apart and continued from Florida Avenue, then Boundary Street, to the northern line of the park.

[See the following 1861 map, a map we extolled several months ago:

To the east of the Gilman tract was a narrow strip of land known as the Prather tract. East of this was Moore’s Lane, now Second Street, and still to the east was the tracts of the Moores, George and David, covering the territory as far east as the present location of Lincoln Avenue [now Lincoln Road], on which was located Harewood Hospital, another hospital of considerable note during the civil war.

T.R. Senior, who was commissary at Campbell Hospital, returned to the city some twelve years after the war closed and purchased a residence at the corner of Elm and Second Streets, where he now resides. Members of the family of David McClelland now occupy the old homestead on Second Street.

Following the close of the war it became necessary to provide for such of the freedmen as were in need of assistance. Campbell General Hospital was occupied by the freedmen until August 16, 1869, when the patients were transferred to the new Freedman’s Hospital, which has been erected in connection with Howard University.

The property upon which Freedman’s Hospital stands consisted of a tract of 150 acres and was purchased from John A. Smith. In April, 1867, Howardtown was laid out and soon after some 500 lots were sold, and at this time it seems that the idea was conveyed that streets would be opened to the south through the Miller tract. In April, 1870, the Howard University purchased the Miller tract, and laid out streets to connect the streets of Howardtown with the city streets, and a little later built four houses on the line of what is now known as Fourth Street and in 1872 subdivided the Miller tract, but for some reason the plat was not recorded.

In 1873 the Miller tract was sold by Howard University to A[ndrew] Langdon, and a short time afterward A[mzi] L[orenzo] Barber, formerly secretary of Howard University, became associated with Langdon and hs partner, and by arrangements with D[avid] McClelland, all of the three tracts known as the Miller tract, the McClelland tract, and the Gilman tract were united and subdivided, and in June, 1873, a subdivision known as Le Droit Park was placed on record in the surveyor’s office. A subsequent plat was filed some eighteen months later, in which the proprietors of the subdivision declared it to be their purpose and intention to retain and control the ownership of all the streets platted, and the right to inclose the whole or any portion of the tracts or tract included in the subdivision and to locate and control all entrances and gates to the same.

During the autumn of 1876 A. L. Barber & Co. commenced the erection of fences across the north line of Le Droit Park, and from this time until August, 1891, fences were maintained along the northern line of the park. From 1886 to 1891 frequent fence wars were in operation. The fence across what is now Fourth Street would be removed by one party, and the opposing party would secure an injunction and restore it. This mode of procedure was repeated at various times until in 1901 a compromise verdict was agreed upon by the two factions and the fence was removed, Fourth Street was improved north of the park, and the streets of the park passed into the control of the city after a period of some eighteen years of private ownership.

The organization of Le Droit Park, under the limitations of the plat filed in 1873, was a peculiar experiment, that of the founding of an independent suburb adjoining the city. the southern line of the park was inclosed with a handsome combination iron and wood fence, some of which may now be found on the southern line of the McClelland property. Buildings were erected with plenty of room around them, and during the period from 1873 to 1885 the larger part of the buildings were planned and erected by James H. McGill. Double houses were quite common, but it was not until 1888 that such a thing as a row of houses were known in the park.

Before control of the streets was surrendered to the city the conditions existing in the park resembled closely those found in small country towns. Many of the inhabitants owned cows, which were pastured upon the vacant lots; the women “went a-neighboring,” and the social life savored strongly of a village, and yet it was near the city. The express and telegraph messengers, however, always collected of residents an extra fee for the reason that they lived out of the city.

With the opening of the streets and the introduction of street cars the park soon lost its former characteristics and became part of the city with all of its advantages and disadvantages. The opening of Rhode Island Avenue [from Florida Avenue eastward] spoiled in a measure the former beauty of the McClelland and Gilman homesteads, although there is still much more ground remaining in both of these old tracts that many people would care to own. The opening of Fifth Street will, to some extent, divide the traffic which now finds a way through Fourth Street. Sixth Street ends at Spruce Street [now U Street], and further progress seems barred by the residence, 601 Spruce Street, and there seems no immediate chance of the extension of Third Street above its present limit [at V Street??], where progress is barred by a high fence decorated with the advertisement of a prominent firm.

Former Familiar Street Names.

The old names of the streets of the park, such as Harewood Avenue [now Third Street], Maple Avenue [now U Street], Moore’s Lane [later Le Droit Avenue, then Second Street], Linden Street [now Fourth Street], Larch Street [now Fifth Street], Juniper Street [now Sixth Street], and Bohrer Street [still extant], are nearly forgotten, and have passed away with the fence and its period. The names of the city streets have taken their places, and with the growth of the population the country life and country scenes have given way to those of the city.

Civic Associations Past

Gen. William Birney lived in the mansard-roofed duplex on Anna J. Cooper Circle.

The LeDroit Park Civic Association meets tonight, following a long tradition of meetings to improve the neighborhood. Take a look at this newspaper article from the National Republican published on March 26, 1881:

Improvements Proposed by the Property Owners.

In response to a call issued, there was a very full attendance of the members of Le Droit Park Property Owners’ Association last night in the park. The meeting was called to order by Mr. W. Scott Smith1, the president of the association, who proceeded to state what had been done since the last meeting to promote the interests of the park and the large number of residents living therein. The first business before the association was the election of officers for the ensuing year. On motion of General W. W. Birney2, Mr. W Scott Smith was unanimously re-elected president of the association, Colonel O. H. Irish3 was nominated and elected vice-president; James H. McGill4, secretary; J. J. Albright5, treasurer, and E. B. Barnum6 the additional member of the executive committee. The president said he had recently had an interview with the District Commissioners, and the lighting of two additional gas lamps in the park had been ordered. He had seen the Major and Superintendent of Police about giving the park better police protection, and had received assurances that the matter should receive prompt attention, and an officer detailed specially for night duty in the park.

General Birney submitted a motion, which was adopted, that a vote of thanks be extended to the president of the association for his active efforts during the past year in behalf of the park.

The question of opening a new street on the east side of the Park, running from Boundary street [now Florida Avenue] through to the Soldiers’ Home, then came up, and gave rise to considerable discussion, all concurring in the opinion that such a street was needed. A resolution was the offered and adopted that the members of the association will co-operate heartily with the District Commissioners in securing the opening of such a street and road, and instructing the executive committee to take steps to make effective such co-operation. Attention was directed to the fact that all the houses and a large amount of property in the Park were greatly exposed and jeopardized in case of a fire by the action of the water department in shutting off the pressure of water between the hours of midnight and five o’clock a.m., and thus practically preventing the flow of water in the park. The executive committee were directed to look in the matter and endeavor to have it remedied as soon as possible. The need of a fire-engine in the northern section of the city was regarded as very pressing. After discussing various other matters and directing that rules be prepared for the government and guidance of the special day-policemen, the meeting adjourned.

References

- Private secretary to the Secretary of the Interior; resident of 525 T Street NW. Halford, A. J. Official Congressional Directory. Washington: GPO, 1900.

- Civil War general; resident of 1901 Third Street NW. Read more at Wikipedia.

- Head of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing among other accomplishments; resident of 1907 Third Street NW. National Republican. Washington, Jan. 13, 1879 and Richardson, F. A. Congressional Directory. Washington: GPO, 1880.

- Architect of LeDroit Park.

- Wealthy coal distributor. Cutter, Library Journal. Vol. 17. New York: ALA, 1892.

- Tailor and clothier, E. B. Barnum & Co.; resident of 1883 Third Street NW. Boyd, William Henry. Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia. Washington: Boyd, 1887.

1922 Third Street Revised

On Thursday ANC1B will vote on the revised proposal for 1922 Third Street. The new proposal, pictured above, modifies the scale of the proposed new townhouse (on the left). This part of the project was by far the most controversial, as the previous design (its outline dotted above) called for structure taller and much deeper than the adjacent townhouses.

In fact this revised concept reduces the townhouse size significantly compared to the original concept (dotted below). Another nice feature is the articulation added to the side of the townhouse. Two bays extend out from the side, as does an ornate chimney, much like others in the neighborhood.

These elements combine to produce a structure less visible from the north side of the property on U Street. The developer has shortened the rear addition to allow the historic carriage house to stand out more on its own. The addition’s architectural style resembles that of the main house more closely than the previous design, which combined elements of both the main house and the carriage house.

The developer explained the changes in his own words:

We reduced the size, footprint, height, of the townhouse portion of the plan to address concerns about the mass of this portion in the original concept. The height of the townhouse has been reduced to match the height of the neighboring property and is now below the height of the main structure. The depth of this portion has also been reduced by approximately 30 feet. Further, the profile has been revised to step down towards the rear of the site to increase light to adjacent areas. The result of these combined actions have reduced the mass of the building by almost 40% and a mass of building that is drastically smaller than what would be allowed by-right on the adjoining parcels to the south.In addition to the reduced massing, we eliminated 2 units in the townhouse portion, thereby reducing the overall number of units from 14 to 12 total units.

The reduced number of units, with the provision of 4 parking spaces, has allowed for an increased parking ratio that is in line with other residential uses in the R-4 zone. This new ratio now eliminates the need for a historical parking waiver.

We have articulated the side of the townhouse portion to be more compatible with the surrounding urban character and to give more visual interest to the side elevation.

The addition to the main structure has been redesigned to be more compatible with the character of the existing building. In addition, this revision has allowed for greater views of the historic carriage house from all angles.

We have also learned that the current front porch of the existing building is not historically accurate and we have subsequently redesigned this element to more closely resemble the historic structure’s original porch.

Indeed the current front porch (first image below) is inconsistent with James H. McGill’s original design published in 1880 (second image below).

The developer will present this revision concept to the ANC on Thursday night at 7 pm on the second floor of the Reeves Building at 14th and U Streets. After the developer’s presentation, the commission will allow the public to ask questions (you can always frame your comment in the form of a question) and will then vote to support or to oppose the project. The ANC will forward its opinion to the Historic Preservation Review Board, which will hold a hearing on this revised concept on Thursday, April 22 at 10 am at One Judiciary Square (441 Fourth Street NW), Room 220 South.

Old Maps: The Map that Saved the Capital (1859-1861)

This is the second in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park. Read the first post, The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859).

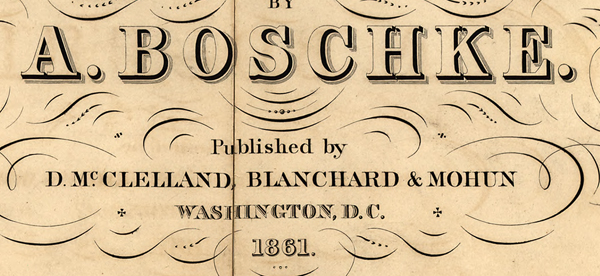

Just a few years after German cartographer Albert Boschke finished his detailed map of Washington City, he completed a map covering the entire District of Columbia. The 1861 map depicts the area around what is now LeDroit Park to be the properties of C. Miller, D. McClelland, and Z. D. Gilman. The original advertisement for LeDroit Park, entitled Le Droit Park Illustrated, also mentions the inclusion of the Prather property, which is not labeled on the map.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Interestingly enough, David McClelland, an engraver, is listed as one of the publishers of the map, so we can assume that he ensured the accuracy of the parcels around his home in what was to become LeDroit Park.

Mr. McClelland continued to live at 301 Boundary Street long after LeDroit Park began to sprout up around him. In fact, Mr. McClelland sold part of his property to form the neighborhood and James H. McGill, architect of LeDroit Park, designed his home, which stood where the United Planning Organization (the old Safeway) now stands.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Mr. McClelland possessed the most accurate map of the nation’s capital. In the hands of the Confederate Army, it could provide a detailed plan for marching on the capital city. In the hands of the Union Army, it could provide a detailed plan for fortifying the capital city. Mr. McClelland knew the value of what he had and unsuccessfully tried to sell it to the War Department, which got a hold of it anyway.

A National Geographic article from 1894 recounts the history of the Boschke map and trouble it caused Mr. McClelland:

At the outbreak of the [Civil W]ar the United States had no topographic map of the District, the only topographic map existing being the manuscript produced by Boschke. He sold his interest in it to Messrs Blagden, Sweeney, and McClelland. Mr McClelland is an engraver, now seventy-four years old, living in Le Droit park. He engraved the Boschke map, which was executed in two plates. With his partners, he agreed to sell the manuscript and plates to the Government for $20,000. Secretary of War [Edwin] Stanton, not apparently understanding the labor expense of a topographic map, thought that $500 was a large sum. There was, therefore, a disagreement as to price. After some negotiations, Mr McClelland and his partners offered all the material, copper-plates and manuscript, to the Government for $4,000, on condition that the plates, with the copyright, should be returned to them at the close of the war. This offer also was refused. There then appeared at Mr McClelland’s house in Le Droit park a lieutenant, with a squad of soldiers and an order from the Secretary of War to seize all the material relating to this map. Mr McClelland accordingly loaded all the material into his own wagon and, escorted by a file of soldiers on either side, drove to the War Department [next to the White House] and left the material.

The Committee on War Claims compensated Mr. McClelland in the amount of $8,500 and never returned the maps.

To the northeast of the McClelland estate sat the narrow pasture of Mr. George Moore, from whose house all the way west to Georgia Avenue (then Seventh Street Road) stood a large grove of trees. Today the grove is covered by the south end of the Howard campus and by Howard University Hospital. In late August and early September of 1861, however, the grove served as a camp for the First New York Cavalry. Lieutenant William H. Beach recounted in his memoirs his stay at the Moore farm:

[T]he companies formed and took up their march … to a part of the city now known as Le Droit Park. This section now well built up was then open country the farm of Mr. Moore. In a grove of scattering scrub oaks near the present intersection of Fourth and Wilson [now V] streets the camp was established and named Camp Meigs.

….

Mr. and Mrs. Moore and their two daughters, with two or three colored servants, were well-to-do and hospitable people of Union sympathies. Some of the officers messed in the house and a few averse to living in a tent had rooms here. On a recent visit the writer found Mrs. Moore still living, about eighty five years of age, and her two daughters with her. Her mind was clear, and her memory of the officers and some of the men very accurate, and not unkind, although there were at that time many things that were annoying to the family.

Next: The Civil War ends and Howard University is established with land that a trustee, Amzi Barber, sells to… himself.

Recent Comments