Just who was Ernest Everett Just?

An academic’s prestige is usually measured by the degree to which his peers admire his work. Any job where success depends on reputation is bound to be a difficult and political career. Howard biologist Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941), who lived at 412 T Street in LeDroit Park, faced a constant struggle for recognition for his groundbreaking work in biology in the early 20th century.

I occasionally give history tours of the neighborhood. My tour touches on two major themes: the neighborhood’s eclectic architecture and the prominent black Americans who lived in LeDroit Park. I had never heard of Just before moving to LeDroit Park, but in researching topics for my tour I came across a 1995 postage stamp commemorating him. This makes him the first of two LeDroit Park residents featured on postage stamps.

Two months ago, a neighbor who was a researcher at Howard University recommended Kenneth Manning‘s 1983 biography of Just. He assured me that the book, entitled Black Apollo of Science, detailed all the administrative problems at Howard that still exist to this day.

I picked up the book hoping to read historical accounts of LeDroit Park while Just lived in the neighborhood. Though there was very little about the neighborhood, the book provided interesting stories about Howard University’s administrative and financial troubles during the early 20th century.

The book was light on LeDroit Park and Washington because Just himself increasingly disliked teaching at Howard and the pervasive racism he faced living in the United States. In the 1920s, midway through his career, Just began to spend more time conducting research at research institutes in Berlin; Naples; and Roscoff, France. He deliberately avoided returning to the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where he felt he was socially isolated because of his race. Just saw Europe as an escape from racism he faced at home.

In Europe Just could finally attend the same operas he had seen advertised in Washington’s whites-only venues and he could travel and book hotels without worrying that his reservations would be rejected due to Jim Crow.

Whether Just was pursuing his PhD at the University of Chicago or conducing research in Massachusetts or Europe, his wife and children remained in LeDroit Park at 412 T Street. But as Just eventually grew apart from the United States, he also grew apart from his wife. Just took several lovers in Europe during his research stints and he eventual filed for divorce from his wife Ethel in the late ’30s. This was a formality, though, as their love had died many years ago.

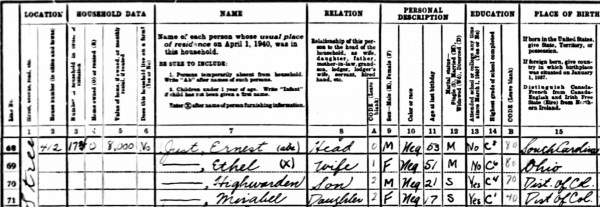

Though Just was in France at the time of the 1940 census, the census ledger lists him as the absent head of household at 412 T Street.

The Just family stood out for its educational attainment. Notice that in column 14, Just is listed as having completed eight years of college, an outstanding accomplishment even by today’s standards. His wife had finished six years of college, his son four, and his daughter Maribel, aged 17, was in her first year of college.

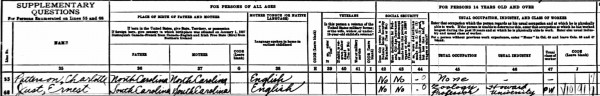

Out of pure luck, Just was listed on line 68, which was one of two lines per page that the Census Bureau selected for supplmentary questions.

Here Just stands out again. Though most LeDroit residents were listed as maids, porters, or laborers, Just’s profession is listed as “Zoology professor” at Howard University.

Just’s life was not easy. He grew up in poverty and his father died when Just was a child. Just’s mother was a teacher who valued his education dearly and she sent him as a teenager to a boarding school in New Hampshire. During his time at boarding school, his mother died, leaving Just orphaned but independent.

After boarding school, he proceeded to Dartmouth to study classics and biology, the field to which he devoted his entire career. Since few universities at the time would hire black researchers or professors, Just took a position at Howard University and in 1912 became the head of Howard’s Department of Zoology.

The Howard position was Just’s main source of income for the rest of his life and he used it, along with a few private grants, to fund his research in Massachusetts and Europe. Though Just kept his position at Howard until his death, he spent many semesters and summers studying marine biology far away from Washington. Howard, it seems, was only a source of income for Just, as he frequently battled with the university’s administration for more equipment, more funding, and more research time.

Howard’s presidents, especially Mordecai Johnson, demanded that Just focus less on research and more on teaching and building a graduate zoology program.

Johnson wasn’t the only person pressuring Just. White philanthropists who wanted to raise academic achievement and living standards of American blacks funded Just’s work with the goal that he would train aspiring black scientists and doctors. Their hope was that Just would train black biology students so they could study medicine and return to the rural south where white doctors would not treat black patients.

Just, however, wanted philanthropic funding to support his biological research efforts, not his teaching efforts. Just preferred research and appeared far more interested in advancing the human understanding of cell biology.

Old letters Manning uncovered reveal that Just held a low opinion of Howard undergraduates during his tenure. Just thought teaching biology to them was a waste of time and would distract him from important research.

To teach or to research? This is an old academic controversy. Many professors prefer to conduct research because they find it more intellectually satisfying and because it builds their careers, expertise, and reputations. At universities that rely heavily on tuition fees for their income, administrators realize that teaching is an important source of income.

For Just, the written correspondence between him and various philanthropies shows that because he was black, he was expected to carry the herculean task of advancing both the human understanding of biology and the welfare of his race— a burden his white benefactors did not place on white scientists. These expectations, though well intentioned, continually hindered Just’s career as his appeals for research grants rarely bore fruit. Various foundations and Howard administrators urged Just to spend more effort building a biology program and producing trained biologists.

Just found a warmer reception in Germany, Italy, and France, where scientists were more eager to collaborate with him and build on his work. While in Europe, Just dated several women. He even established residence in Latvia briefly so he could quickly file for divorce from his wife in Washington. He eventually decided to mary his German mistress and start a life in Europe, even if it meant resigning his post at Howard and living in penury in Europe.

Failing to win grants, though, Just held onto his Howard position as his sole source of income. Just’s time in Europe was productive. He published his most renowned works on cell biology and cell fertilization during this self-exile.

His new-found haven across the Atlantic didn’t remain peaceful for long. Though he had tried to escape racism in the United States, Nazi violence had made Berlin inhospitable. In Italy, Just’s appeals to Mussolini for research funding went nowhere and Italian biology conferences became fascist propaganda events.

Just’s final European post in France came under Nazi control and Just was ordered to leave. The advancement of fascism eventually made this European exile untenable. Sadly, everywhere Just went, some virulent -ism— racism, fascism, Nazism— eventually caught up with him.

Just returned to the United States with his new wife and newborn child. His new wife and child settled in New Jersey, but Just had to return to work for pay at Howard. Suffering from pancreatic cancer, Just stayed with his sister Inez at 1853 3rd Street, here in LeDroit Park. His health was in rapid decline and in October 1941 Just died.

Despite having overturned a ruling theory of cell fertilization, Just never fully received the professional recognition he desired and deserved. He was always tied to Howard, even though he wanted desperately to leave to focus solely on research. Howard tied him to Washington, a city whose segregation degraded him. Washington also tied him to a wife he no longer loved.

Manning’s book is very well researched and combs through many of Just’s letters to colleagues, mentors, friends, and lovers. It tells a fascinating account of race relations in America, the history of biology research, and one man’s unhappy task facing down all these problems.

Manning was able to weave these threads of science, race, academia, and Just’s personal life into a unified and compelling work accessible to the general reader. Happy endings are the work of fiction writers; Just’s story is more poignant because it recounts a life marked by great successes and great disappointments.

Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just

Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just

By Kenneth Manning

1983, Oxford University Press. 330 pages.

[Amazon] [DC Public Library]

Mieke En De Heikrekels Zou Dat Liefde Zijn https://qz.joyous-being.biz/23.html Nickerbocker Lustobjekt Ode An A Moderne Hex

, .

, .

Grrr, I’ve a blog on my website and it sucks. I actually

removed it, but may have to bring it back. You gave

me inspiration!

Keep on writing!

rkn447