Old Maps: The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859)

This is the first in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park.

When the Federal Government established the national capital, it was to be located within a 100-square-mile diamond straddling both sides of the Potomac. In fact, the City of Washington was just one of several established cities and settlements in the nascent Federal District, later called the District of Columbia. The City of Washington, as defined by Congress and Peter L’Enfant’s plan, was bounded by the Potomac River and Rock Creek to the west, the Anacostia River to the south and east, and by Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue) to the north. LeDroit Park sits just north of Florida Avenue, in what was originally the rural Washington County, District of Columbia. The District also included the City of Georgetown, the City of Alexandria, and Alexandria County (now Arlington County, Virginia).

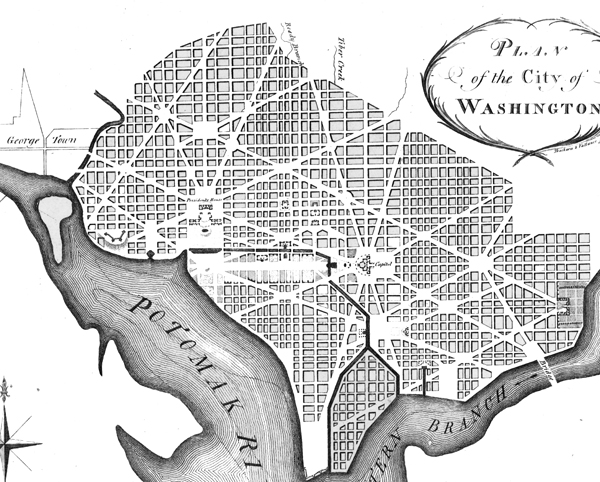

The map below, dating from 1792, was the first printed version of the L’Enfant Plan (as amended by Andrew Ellicott) for the City of Washington. Notice that its northern boundary coincides with what is now Florida Avenue. LeDroit Park now sits just to the west of what is marked as “Tiber Creek”. The creek, also called Goose Creek before the founding of the city, originally ran between First and Second Streets NW through Bloomingdale all the way to what is now Constitution Avenue NW, and westward toward the Washington Monument grounds, where it emptied into the Potomac River. Much of the creek is now buried in pipes beneath the city.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

(We have a reliable method of identifying the future LeDroit Park on old maps of Washington: look for New Jersey Avenue NW, which runs diagonally to the northwest from the Capitol. Directly north of where it ends at the city’s border is where LeDroit Park would later be built.)

The capital city grew slowly over the coming decades with new residents, including government workers and Members of Congress, housed in newly constructed houses and boarding houses near the White House and Capitol, respectively. The difficulty in finding enough skilled labor to build a capital city required the leasing of slaves, who were instrumental in constructing many of the grand public buildings that stand today.

It would be a mistake to look at the map above and assume that all the new streets and canals were built together. In fact, the L’Enfant Plan was just that, a plan. The grand, spacious avenues required the clearing of trees and brush after a tedious survey to match the ground with the map.

In fact, by 1842 so much of the city was incomplete that a visiting Charles Dickens belittled Washington as a “city of magnificent intentions” marked by

spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.

Whereas the global financial markets of today allow developers to develop large tracts of land at once, 19th-century cities had to be built piecemeal with speculation limited to small projects. LeDroit Park was no different: only several houses and only a few streets were built at first with the rest to come later.

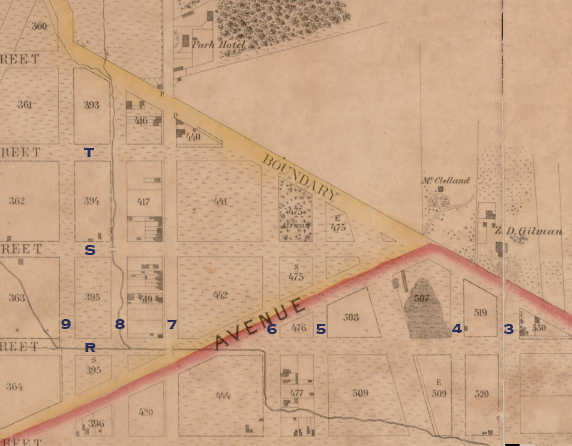

From 1856 to 1859, German cartographer Albert Boschke charted the District hoping to sell his maps to the U.S. Government. His 1859 map of the City of Washington (below) provided illustrative evidence supporting Charles Dickens’s sneer. Much of Washington, especially its northern reaches near what was to become LeDroit Park, sat undeveloped with only a few cleared streets.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

The only clear north-south street was Seventh Street, which connected the city with the rural county and stretched into Maryland (albeit under different names). At R Street— if one could call it a street— it crossed an open creek that ran through the right-of-way.

Seventh Street’s primacy as the main north-south thoroughfare actually contradicts the intention of the L’Enfant Plan, whose Baroque determination to provide a “reciprocity of sight“, plotted Eighth Street, not Seventh Street, as the more important axis. In fact to this day the right-of-way of Eighth Street is fifteen feet wider than those of Seventh and Ninth Streets, even though Eight carries only a fraction of the traffic burden that the parallel streets carry.

It is difficult to enforce one artistic vision on a democracy; the shifting of axes, from Eighth to Seventh, merely reflects the fact that cities are shaped by their inhabitants in ways the founders never anticipate. The future LeDroit Park was no different.

Next: Alfred Boschke maps the entire District and a future LeDroit Park resident prints it, only to have it seized at gunpoint.

I really like this Boschke map, although the download option doesn’t appear to work…although maybe it is just my computer.

Some great references to learn about the planning and development of DC I recommend include:

Worthy of a Nation – F. Gutheim

Designing the Nations Capital: The 1901 Plan – Commission of Fine Arts

Washington: How Slaves, Idealists & Scoundrels Created the Nation’s Capital – F. Bordewich

Creating the Nations Capital – F. Bordewich

Grand Avenues: The Story of L’Enfant – S. Berg

Capital Speculations – S. Luria

Washington Burning – L. Standford

Capital Losses – J. Goode

Washington through two Centuries – forget author

I might be off on the names of some of these authors, but these have all been great books to read up on DC. I have read through most of them and find them all invaluable references!

[…] This is the second in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park. Read the first post, The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859). […]

[…] neighborhood is just outside the original L’Enfant city. In L’Enfant’s time, the main form of transportation was the human foot, so a city […]