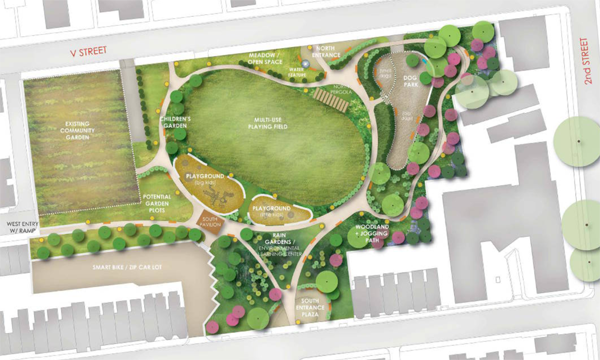

Park Design Meeting Tonight

The city is in the process of finalizing the design for the new park, but there are still opportunities for public input.

Come out tonight at 6:30 to see what the latest proposal has to offer in terms of pavement materials, benches, pavilions, and playground equipment.

April 14th at 6:30 pm

St. George’s Church

Second and U Streets NW

Old Maps: The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859)

This is the first in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park.

When the Federal Government established the national capital, it was to be located within a 100-square-mile diamond straddling both sides of the Potomac. In fact, the City of Washington was just one of several established cities and settlements in the nascent Federal District, later called the District of Columbia. The City of Washington, as defined by Congress and Peter L’Enfant’s plan, was bounded by the Potomac River and Rock Creek to the west, the Anacostia River to the south and east, and by Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue) to the north. LeDroit Park sits just north of Florida Avenue, in what was originally the rural Washington County, District of Columbia. The District also included the City of Georgetown, the City of Alexandria, and Alexandria County (now Arlington County, Virginia).

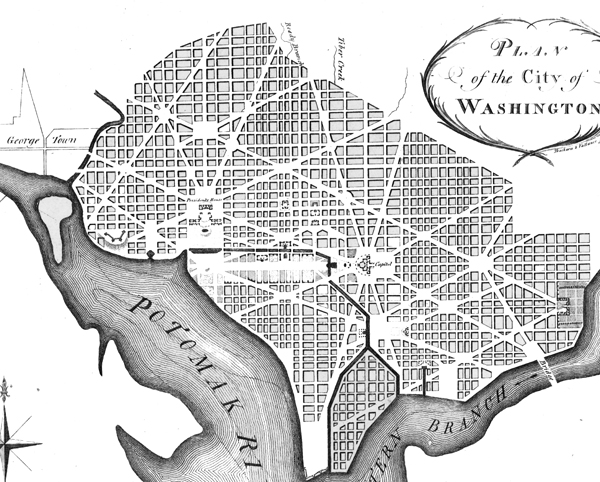

The map below, dating from 1792, was the first printed version of the L’Enfant Plan (as amended by Andrew Ellicott) for the City of Washington. Notice that its northern boundary coincides with what is now Florida Avenue. LeDroit Park now sits just to the west of what is marked as “Tiber Creek”. The creek, also called Goose Creek before the founding of the city, originally ran between First and Second Streets NW through Bloomingdale all the way to what is now Constitution Avenue NW, and westward toward the Washington Monument grounds, where it emptied into the Potomac River. Much of the creek is now buried in pipes beneath the city.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

(We have a reliable method of identifying the future LeDroit Park on old maps of Washington: look for New Jersey Avenue NW, which runs diagonally to the northwest from the Capitol. Directly north of where it ends at the city’s border is where LeDroit Park would later be built.)

The capital city grew slowly over the coming decades with new residents, including government workers and Members of Congress, housed in newly constructed houses and boarding houses near the White House and Capitol, respectively. The difficulty in finding enough skilled labor to build a capital city required the leasing of slaves, who were instrumental in constructing many of the grand public buildings that stand today.

It would be a mistake to look at the map above and assume that all the new streets and canals were built together. In fact, the L’Enfant Plan was just that, a plan. The grand, spacious avenues required the clearing of trees and brush after a tedious survey to match the ground with the map.

In fact, by 1842 so much of the city was incomplete that a visiting Charles Dickens belittled Washington as a “city of magnificent intentions” marked by

spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.

Whereas the global financial markets of today allow developers to develop large tracts of land at once, 19th-century cities had to be built piecemeal with speculation limited to small projects. LeDroit Park was no different: only several houses and only a few streets were built at first with the rest to come later.

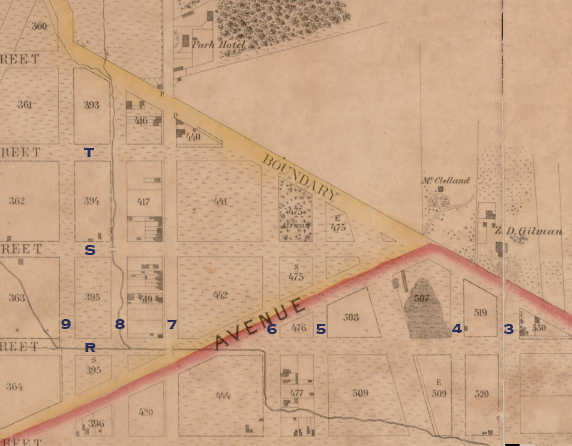

From 1856 to 1859, German cartographer Albert Boschke charted the District hoping to sell his maps to the U.S. Government. His 1859 map of the City of Washington (below) provided illustrative evidence supporting Charles Dickens’s sneer. Much of Washington, especially its northern reaches near what was to become LeDroit Park, sat undeveloped with only a few cleared streets.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

The only clear north-south street was Seventh Street, which connected the city with the rural county and stretched into Maryland (albeit under different names). At R Street— if one could call it a street— it crossed an open creek that ran through the right-of-way.

Seventh Street’s primacy as the main north-south thoroughfare actually contradicts the intention of the L’Enfant Plan, whose Baroque determination to provide a “reciprocity of sight“, plotted Eighth Street, not Seventh Street, as the more important axis. In fact to this day the right-of-way of Eighth Street is fifteen feet wider than those of Seventh and Ninth Streets, even though Eight carries only a fraction of the traffic burden that the parallel streets carry.

It is difficult to enforce one artistic vision on a democracy; the shifting of axes, from Eighth to Seventh, merely reflects the fact that cities are shaped by their inhabitants in ways the founders never anticipate. The future LeDroit Park was no different.

Next: Alfred Boschke maps the entire District and a future LeDroit Park resident prints it, only to have it seized at gunpoint.

New Business

What’s up at 1970 Second Street? The façade recently received a new coat of paint and the first floor has been renovated.

The location currently holds a Retail B liquor license (ABRA-003439) allowing the establishment to sell beer and wine (not liquor) in sealed containers to be consumed elsewhere. This suggests the house could host a convenience store, but the proprietor may have plans to apply for a completely different license altogether.

Eye in the Sky (1988 – 2009)

What a difference twenty-one years make. Below are two satellite photos of LeDroit Park— one taken in 1988 and the other taken in 2009. Toggle back and forth between the two to see how the neighborhood’s footprint has changed.

There are a few noticeable changes:

- Howard University Hospital built an annex behind the main hospital building.

- The entire block bounded by Fourth Street, Fifth Street, V Street, and Oakdale Place is now a multi-level parking garage.

- In 1988, the 500 block of U Street looked gap-toothed; new houses have since been built to fill out the entire north side of the street.

- Street intersections have been replaced with concrete while the roadways remain asphalt.

- The tree canopy is much more expansive now (or the 1988 photo was taken in the winter).

- Houses have been built on the once-vacant land around the northeast corner of Fourth and U Streets.

- The intersection of T Street, Sixth Street, and Florida Avenue has been reconfigured, making way for the pocket park home to the LeDroit Park entrance arch.

- The Schoolhouse Lofts condo building has since been built at Second and V Streets.

Did we miss anything?

Old Street Names

Careful observers occasionally spot the old street signs adorning a few of the light poles in LeDroit Park. When the neighborhood was originally planned, most of the streets were named after trees. LeDroit Park’s street system didn’t fit with the L’Enfant Plan in either name or alignment—much to the dismay of the District commissioners—and the street names were eventually changed to fit the naming and numbering system.

A perusal of old maps reveals that the street names changed over time, not all at once. Elm Street is the only street that has retained its name. Since your author lives on Elm Street he has learned to respond to puzzled faces that know that Elm doesn’t fit the street naming system: “It’s kinda like U-and-1/3 Street”.

Anna J. Cooper Circle didn’t have a name at all until 1983, when it was restored to its circular form after a decades-long bisection by Third Street.

Just outside of LeDroit Park, the city renamed a few streets as well: 7th Street Road became Georgia Avenue and Boundary Street, the boundary of the L’Enfant Plan, became Florida Avenue.

Here is a table matching the current street names with their previous names.

| Old Name | Current Name |

| Le Droit Avenue | 2nd Street |

| Harewood Avenue | 3rd Street |

| Linden Street | 4th Street* |

| Larch Street | 5th Street |

| Juniper Street | 6th Street |

| Elm Street | (same) |

| Boundary Street | Florida Avenue** |

| 7th Street Road | Georgia Avenue** |

| Oak Court | Oakdale Place |

| Maple Avenue | T Street |

| Spruce Street | U Street |

| Wilson Street | V Street** |

| Pomeroy Street | W Street** |

| (unnamed before 1983) | Anna J. Cooper Circle |

| * For a short period, 4th Street was called 4½ Street. ** Though these streets were just outside the original LeDroit Park, we have included them for reference. |

|

Signs bearing the old street names have reappeared in the neighborhood, and according to the Afro-American, were put up in 1976: “The LeDroit Park Historic District Project was instrumental in getting the D.C. Department of Transportation to put up the old original street names for this Historic District Area under the present street name signs”.1

Unfortunately, some of the signs are showing their 33 years of weather, as this sign at Third and U Streets shows.

Eventually these signs will have to be replaced, but rather than placing the old names onto modern signs using a modern typeface, we suggest something that evokes the history without being mistaken for the current street name:

White text on a brown background is the standard for street and highway signs pointing to areas of recreation or cultural interest. Seattle started using the color scheme to mark its historic Olmsted boulevards and New York has long used the combination for street signs in its historic districts. The adoption of this style of sign would alert visitors and residents to the neighborhood’s historic identity while the different color and typeface would prevent confusion with the actual street names (U St NW in this case). Typographers would be pleased by the use of Big Caslon Medium, a serif typeface based on the centuries-old Caslon typeface.

- Hall, Ruth C. “Historic Project”. Washington Afro-American. 1 May 1976.

Recent Comments