How LeDroit Park Came to be Added to the City

The following is a Washington Times article from 1903. The article explains some of the early history of the neighborhood and even includes three photos, the first of which was misidentified as Fifth Street, though we have actually matched it up with Second Street. We have included a few links to related information.

Second Street opposite the Anna J. Cooper House.

HOW LE DROIT PARK CAME TO BE ADDED TO THE CITY

Washington Times

Sunday, May 31, 1903For Many Years the Section of Washington Known by That Name Had Practically Its Separate Government and Had All the Characteristics of a Country Town, Although Plainly Within the Boundary Limits. * * *

In that portion of Florida Avenue between Seventh Street and Eighth Streets northwest where the street cars of the Seventh Street line and the Ninth Street line pass over the same tracks, thousands of passengers are carried every day, and probably but a few if any realize the fact that they are passing over a road older than the organization of the city, a road that dates back to the Revolutionary period— the Bladensburg Road, which connected Georgetown with Bladensburg before the location of the National Capital was determined.

The Map on the Wall.

If the people passing this point will note the little frame building occupied by a florist, 713 Florida Avenue northwest, they will observe that in front of these premises and fastened to the blacksmith shop adjoining is a goodly sized signboard on which is painted an old map of this section and showing the intersection of the old Blandensburg Road and Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue. From this map it is seen that Seventh Street Road [now Georgia Avenue] intersects Boundary Street and the old Bladensburg Road at a point about 100 feet east of where the two roads join at an acute angle, and glancing along the lines of Boundary Street and the north lines of some buildings which have been erected in this angle we easily see the direction of the Bladensburg Road and discover that the small building 713 Florida Avenue northwest marks the spot where the Bladensburg Road deflected from Boundary Street and bore off in a northeasterly direction toward Bladensburg.

Once Part of Jamaica Vacancy.

The map referred to is said to be a portion of [the estate named] Jamaica and and Smith’s Vacancy, but if we examine the plats in the office of the Surveyor of the District we will hardly find on file any plats of those sections, but may learn that Le Droit Park was once part of Jamaica and Smith’s Vacancy and possibly a portion of [the estate named] Port Royal. Prior to the cession of the territory now included in the District from Maryland the land known as Jamaica was owned by one Philip R. Fendall, of Virginia. He conveyed this tract of 494 acres on the 12th day of January, 1792, to Samuel Blodgett, jr., of Massachusetts, and from this point the title of the land can be traced down to the present time.

The names attached to the different vacancies establish the names of the various owners of lands adjoining Bladensburg Road at the time it was abandoned as a thoroughfare and taken up as a portion of the farms in that section, and the presence of this old road accounts for some of the peculiar lines in some of the northern boundaries of some of the lots in Le Droit Park. This road crossed Second Street at a point north of Elm Street here. The old plats show Moore’s Vacancy. The road finally joined the present road to Bladensburg at a point where the sixth milestone of the norther line of the District was located.

It is probable that this peculiarly natural boundary of some of the lands which afterward became Le Droit Park may have had something to do with the strange lines which are found in the streets of that suburb, although it was not the intention at the time that Le Droit Park was subdivided to have the streets conform with the city streets.

Site of Campbell Hospital.

During the civil war the territory now contained in Le Droit Park was used as the site of Campbell General Hospital, one of the important hospitals near Washington. The hospital comprised some seventeen separate wooden buildings, erected in the form of a hollow square, with the central portion divided into irregular spaces by buildings cutting across the inclosure and connecting the outside buildings.

The larger dimension of this hospital was fro north to south, and extended from Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue, on the south, to the land occupied for many years as a baseball park, situated south of Freedman’s Hospital, and designated on some of the old maps as Levi Park. From east to west the hospital covered the ground from Seventh Street to what is now known as Fifth Street in Le Droit Park, and it is possible that a portion of the space between Fifth Street and Fourth Street was also included in the hospital inclosure.

The McClelland Residence.

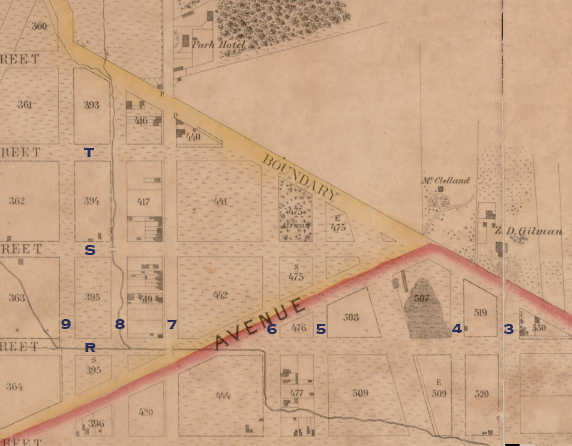

At this time there were only two dwellings in the tract known afterward as Le Droit Park— the McClelland and Gilman homestands. Each included about ten acres of land used for grazing and garden purposes. The McClelland property and the Gilman property were divided by a row of large oak trees which were situated about fifty feet apart and continued from Florida Avenue, then Boundary Street, to the northern line of the park.

[See the following 1861 map, a map we extolled several months ago:

To the east of the Gilman tract was a narrow strip of land known as the Prather tract. East of this was Moore’s Lane, now Second Street, and still to the east was the tracts of the Moores, George and David, covering the territory as far east as the present location of Lincoln Avenue [now Lincoln Road], on which was located Harewood Hospital, another hospital of considerable note during the civil war.

T.R. Senior, who was commissary at Campbell Hospital, returned to the city some twelve years after the war closed and purchased a residence at the corner of Elm and Second Streets, where he now resides. Members of the family of David McClelland now occupy the old homestead on Second Street.

Following the close of the war it became necessary to provide for such of the freedmen as were in need of assistance. Campbell General Hospital was occupied by the freedmen until August 16, 1869, when the patients were transferred to the new Freedman’s Hospital, which has been erected in connection with Howard University.

The property upon which Freedman’s Hospital stands consisted of a tract of 150 acres and was purchased from John A. Smith. In April, 1867, Howardtown was laid out and soon after some 500 lots were sold, and at this time it seems that the idea was conveyed that streets would be opened to the south through the Miller tract. In April, 1870, the Howard University purchased the Miller tract, and laid out streets to connect the streets of Howardtown with the city streets, and a little later built four houses on the line of what is now known as Fourth Street and in 1872 subdivided the Miller tract, but for some reason the plat was not recorded.

In 1873 the Miller tract was sold by Howard University to A[ndrew] Langdon, and a short time afterward A[mzi] L[orenzo] Barber, formerly secretary of Howard University, became associated with Langdon and hs partner, and by arrangements with D[avid] McClelland, all of the three tracts known as the Miller tract, the McClelland tract, and the Gilman tract were united and subdivided, and in June, 1873, a subdivision known as Le Droit Park was placed on record in the surveyor’s office. A subsequent plat was filed some eighteen months later, in which the proprietors of the subdivision declared it to be their purpose and intention to retain and control the ownership of all the streets platted, and the right to inclose the whole or any portion of the tracts or tract included in the subdivision and to locate and control all entrances and gates to the same.

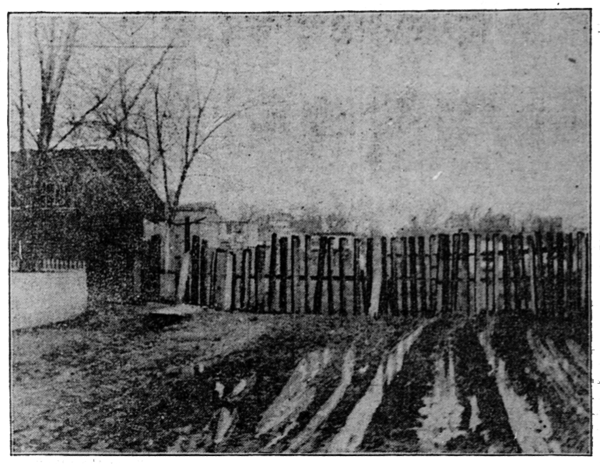

During the autumn of 1876 A. L. Barber & Co. commenced the erection of fences across the north line of Le Droit Park, and from this time until August, 1891, fences were maintained along the northern line of the park. From 1886 to 1891 frequent fence wars were in operation. The fence across what is now Fourth Street would be removed by one party, and the opposing party would secure an injunction and restore it. This mode of procedure was repeated at various times until in 1901 a compromise verdict was agreed upon by the two factions and the fence was removed, Fourth Street was improved north of the park, and the streets of the park passed into the control of the city after a period of some eighteen years of private ownership.

The organization of Le Droit Park, under the limitations of the plat filed in 1873, was a peculiar experiment, that of the founding of an independent suburb adjoining the city. the southern line of the park was inclosed with a handsome combination iron and wood fence, some of which may now be found on the southern line of the McClelland property. Buildings were erected with plenty of room around them, and during the period from 1873 to 1885 the larger part of the buildings were planned and erected by James H. McGill. Double houses were quite common, but it was not until 1888 that such a thing as a row of houses were known in the park.

Before control of the streets was surrendered to the city the conditions existing in the park resembled closely those found in small country towns. Many of the inhabitants owned cows, which were pastured upon the vacant lots; the women “went a-neighboring,” and the social life savored strongly of a village, and yet it was near the city. The express and telegraph messengers, however, always collected of residents an extra fee for the reason that they lived out of the city.

With the opening of the streets and the introduction of street cars the park soon lost its former characteristics and became part of the city with all of its advantages and disadvantages. The opening of Rhode Island Avenue [from Florida Avenue eastward] spoiled in a measure the former beauty of the McClelland and Gilman homesteads, although there is still much more ground remaining in both of these old tracts that many people would care to own. The opening of Fifth Street will, to some extent, divide the traffic which now finds a way through Fourth Street. Sixth Street ends at Spruce Street [now U Street], and further progress seems barred by the residence, 601 Spruce Street, and there seems no immediate chance of the extension of Third Street above its present limit [at V Street??], where progress is barred by a high fence decorated with the advertisement of a prominent firm.

Former Familiar Street Names.

The old names of the streets of the park, such as Harewood Avenue [now Third Street], Maple Avenue [now U Street], Moore’s Lane [later Le Droit Avenue, then Second Street], Linden Street [now Fourth Street], Larch Street [now Fifth Street], Juniper Street [now Sixth Street], and Bohrer Street [still extant], are nearly forgotten, and have passed away with the fence and its period. The names of the city streets have taken their places, and with the growth of the population the country life and country scenes have given way to those of the city.

Old Maps: The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859)

This is the first in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park.

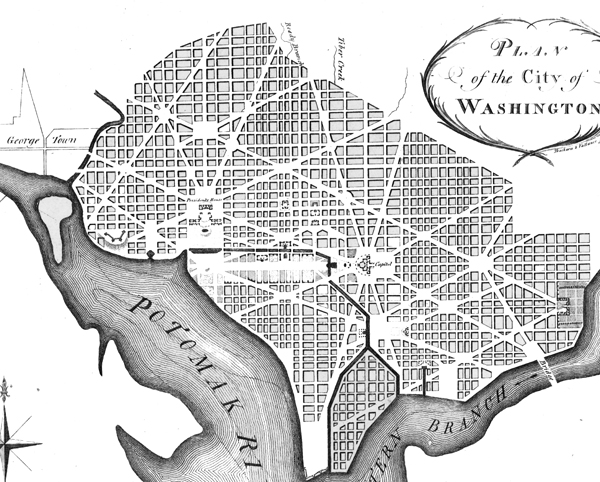

When the Federal Government established the national capital, it was to be located within a 100-square-mile diamond straddling both sides of the Potomac. In fact, the City of Washington was just one of several established cities and settlements in the nascent Federal District, later called the District of Columbia. The City of Washington, as defined by Congress and Peter L’Enfant’s plan, was bounded by the Potomac River and Rock Creek to the west, the Anacostia River to the south and east, and by Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue) to the north. LeDroit Park sits just north of Florida Avenue, in what was originally the rural Washington County, District of Columbia. The District also included the City of Georgetown, the City of Alexandria, and Alexandria County (now Arlington County, Virginia).

The map below, dating from 1792, was the first printed version of the L’Enfant Plan (as amended by Andrew Ellicott) for the City of Washington. Notice that its northern boundary coincides with what is now Florida Avenue. LeDroit Park now sits just to the west of what is marked as “Tiber Creek”. The creek, also called Goose Creek before the founding of the city, originally ran between First and Second Streets NW through Bloomingdale all the way to what is now Constitution Avenue NW, and westward toward the Washington Monument grounds, where it emptied into the Potomac River. Much of the creek is now buried in pipes beneath the city.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

(We have a reliable method of identifying the future LeDroit Park on old maps of Washington: look for New Jersey Avenue NW, which runs diagonally to the northwest from the Capitol. Directly north of where it ends at the city’s border is where LeDroit Park would later be built.)

The capital city grew slowly over the coming decades with new residents, including government workers and Members of Congress, housed in newly constructed houses and boarding houses near the White House and Capitol, respectively. The difficulty in finding enough skilled labor to build a capital city required the leasing of slaves, who were instrumental in constructing many of the grand public buildings that stand today.

It would be a mistake to look at the map above and assume that all the new streets and canals were built together. In fact, the L’Enfant Plan was just that, a plan. The grand, spacious avenues required the clearing of trees and brush after a tedious survey to match the ground with the map.

In fact, by 1842 so much of the city was incomplete that a visiting Charles Dickens belittled Washington as a “city of magnificent intentions” marked by

spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.

Whereas the global financial markets of today allow developers to develop large tracts of land at once, 19th-century cities had to be built piecemeal with speculation limited to small projects. LeDroit Park was no different: only several houses and only a few streets were built at first with the rest to come later.

From 1856 to 1859, German cartographer Albert Boschke charted the District hoping to sell his maps to the U.S. Government. His 1859 map of the City of Washington (below) provided illustrative evidence supporting Charles Dickens’s sneer. Much of Washington, especially its northern reaches near what was to become LeDroit Park, sat undeveloped with only a few cleared streets.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

The only clear north-south street was Seventh Street, which connected the city with the rural county and stretched into Maryland (albeit under different names). At R Street— if one could call it a street— it crossed an open creek that ran through the right-of-way.

Seventh Street’s primacy as the main north-south thoroughfare actually contradicts the intention of the L’Enfant Plan, whose Baroque determination to provide a “reciprocity of sight“, plotted Eighth Street, not Seventh Street, as the more important axis. In fact to this day the right-of-way of Eighth Street is fifteen feet wider than those of Seventh and Ninth Streets, even though Eight carries only a fraction of the traffic burden that the parallel streets carry.

It is difficult to enforce one artistic vision on a democracy; the shifting of axes, from Eighth to Seventh, merely reflects the fact that cities are shaped by their inhabitants in ways the founders never anticipate. The future LeDroit Park was no different.

Next: Alfred Boschke maps the entire District and a future LeDroit Park resident prints it, only to have it seized at gunpoint.

Recent Comments