Our zip code, now with some more white people

Every now and then the Census Bureau or some organization releases a report or new data showing that DC’s demographics changed. A recent analysis of census data found that the 20001 zip code, which covers LeDroit Park, Pleasant Plains, Bloomingdale, Truxton Circle, Shaw, and Mount Vernon Square, saw its non-Hispanic white population increase by 27.2 percentage points from 5.6% to 32.8%. In fact, 20001 made the list of “most-whitened zip codes” in the nation.

Our review of the 2010 census data found that LeDroit Park is 21% white, which is below the figure for the zip code.

What does this mean? Without more information, the report doesn’t mean much other than the unsurprising fact that neighborhood demographics change. This plain answer will dissatisfy some. In a city in which identity is inevitably intertwined with politics, many will feel compelled to read too much into the data for some larger narrative that confirms preexisting social or political views.

However, the reasons that people move into and out of a neighborhood are complicated and there are both push and pull factors, both voluntary and involuntary.

Why a person might leave a neighborhood:

- Your new spouse wants to live elsewhere.

- You graduated from the local university and intend to return to your hometown.

- You dislike too many of your neighbors.

- You got a new job far away.

- The rent has become unaffordable.

- You lost your job and can’t pay any rent.

- You want to retire closer to where your children live.

- Perceptions of crime.

- Divorce.

- Death.

- You want to send your children to school elsewhere.

- You’re pursuing a degree somewhere else.

Why a person might move into a neighborhood:

- You are born and that’s where your parents live.

- You found the perfect home.

- Friends and family are nearby.

- There are people like you nearby.

- You got a new job nearby.

- The area is familiar.

- You’re moving in with friends or relatives.

- Rent is cheaper here than in some other place.

- The neighborhood is visually appealing.

Each person’s story is different, but there is far more at work than the simplistic displacement narrative that gets so much press.

Historic fountains rot away in a local national park

Two century-old DC fountains sit decaying and neglected in the woods of a national park in Maryland. The fountains had been missing from the 1940s until they were rediscovered in the woods of Fort Washington National Park in the 1970s.

The top portion of the McMillan fountain, pictured below, was returned to Crispus Attucks park in the Bloomingdale neighborhood in 1983. In 1992 it was moved back to the fenced-off grounds of the McMillan Reservoir just a few blocks away.

The fountain was installed in 1913 at the McMillan Reservoir as a memorial to Senator James McMillan (R – Michigan), who is more remembered locally for his his ambitious McMillan Plan to beautify Washington. The fountain was dismantled in 1941, when the reservoir was fenced off from the public.

Though the top of the McMillan Fountain had been restored to the reservoir grounds, a Bloomingdale ANC commissioner told me the base of the fountain was in the woods in Fort Washington along with the remains of the fountain that stood at the center of the now-razed Truxton Circle.

I went to Fort Washington in search of these discarded works of art. I asked a park ranger where the fountain was and she drew me a map, saying that it stood in the park’s “dump” and partly behind a fence.

I went to the picnic area nearest the site and walked into the woods a short distance where I found a fence. Behind it stood piles of bricks and other discarded building materials.

Beside the site is a dugout that serves as the back court to Battery Emory, a concrete gun battery built in 1898 to protect the capital city from enemy ships.

As I passed through the unfenced dugout, I immediately spotted few granite blocks that served as the cornerstones of the base bowl. Though they are strewn about the ground, a 1912 photograph can help us identify what pieces went where.

The elements of the fountain were stacked like totem pole. The bottom element features carved classical allegorical heads from whose mouths water gushed into the carved bowls below.

Fence material and tree debris cover the carved granite (left) that stood as the fountain base (right).

The next element of the stack is the fluted base to the top bowl.

Several other large granite stones are stacked and marked with numbers, presumably to help in reassembly.

The site also contains the rusting remains of the fountain that stood at Truxton Circle, which formed the intersection of North Capitol Street, Florida Avenue, Lincoln Road, and Q Street. The circle was built around 1901 and the fountain installed there originally stood at the triangle park at Pennsylvania Avenue and M Street in Georgetown.

Truxton Circle stood at Florida Avenue, North Capitol Street, Q Street, and Lincoln Road from 1901 to 1940, when it was demolished to aid commuter traffic.

A newspaper at the time described it as one of the largest fountains in the city. The circle was removed in 1940 to ease the flow of commuter traffic. At that time, the fountain, which may date to as early as the 1880s, made its way to Fort Washington to rust in the woods.

The metal pedestal (left) held up the fountain bowl whose rim rusts in pieces on the ground (right). Notice the classical egg-and-dart pattern.

The fountain was also noted for the metal grates that stood near its base. Now these grates sit rusting in the woods.

If you want to see the fountain remains for yourself at Fort Washington National Park, go to picnic area C. Beyond the end of the parking lot is a restroom building and behind that is the fountain “graveyard.” A fence encloses part of the site, but you can enter through the large gap down the hillside.

Rather than tossing aside our city’s artistic patrimony, we should aim to restore these treasures to the neighborhoods from which they came. Public art is part of what differentiates cherished neighborhoods from unmemorable places.

These works remind us of the accomplishments and civic-mindedness of generations past and urge us to carry on the tradition of civic improvement for generations to come.

Where is Truxton Circle?

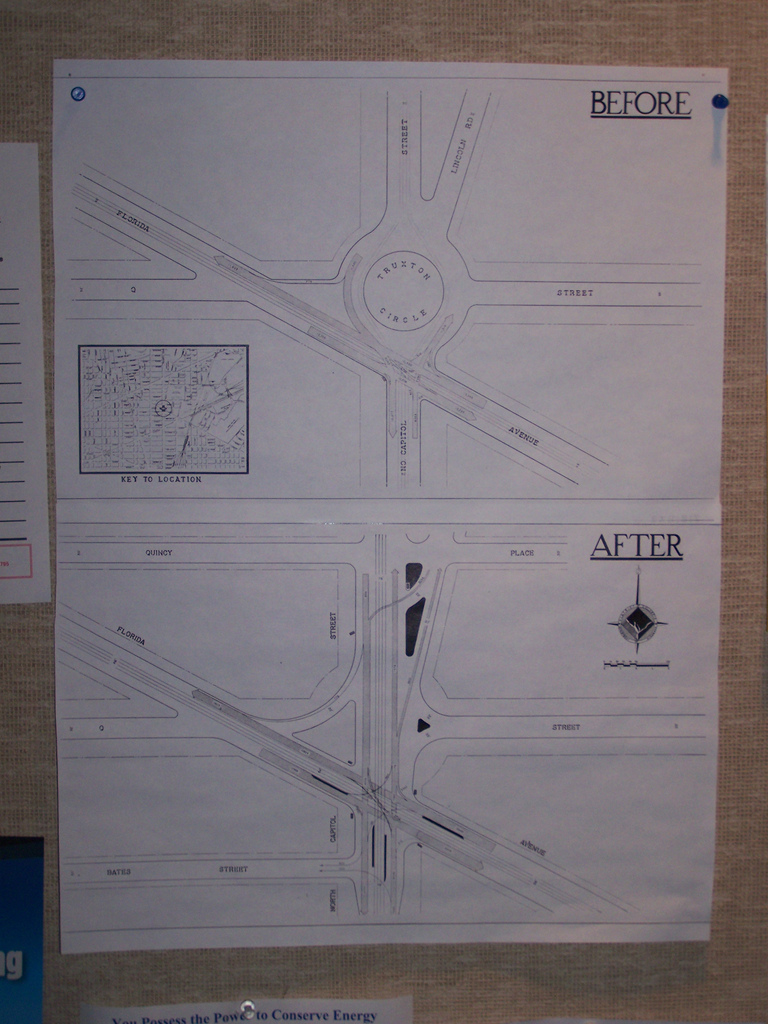

You’ve seen the streetpole banners on Florida Avenue designating the area around North Capitol Street as Truxton Circle. But exactly where is the circle? The circle, pictured above, used to sit right there at the convergence of North Capital Street, Florida Avenue, Q Street, and Lincoln Road.

Urban planning blogger Richard Layman spotted a diagram of the old circle posted on the wall at the offices of DDOT.

In 1940 the District removed the circle and replaced it with a traditional intersection that failed, and continues to fail, to match the elegance of the original circle pictured at the top of this post.

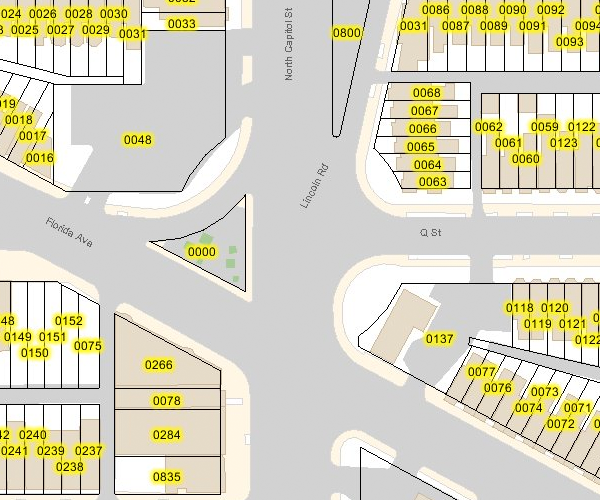

A quick perusal of the DC Atlas, the District’s main online map product, reveals the circle’s imprint on the properties just north of Florida Avenue. It seems that the property lines still accommodate the circle.

Great Truxton's ghost! Proptery lines still show outer limit of the old circle.

Perhaps DDOT will one day resurrect the circle after its seventy-year absence. In 2006, DDOT restored downtown’s Thomas Circle to its original shape, eliminating the almond-shaped cut-through for Fourteenth Street. In the 1980s the District similarly restored Logan Circle, eliminating the Thirteenth Street cut-through. Here in LeDroit Park, Third Street bisected Anna J. Cooper Circle until the District in 1984 restored it to its original circular shape.

Recent Comments