Historic fountains rot away in a local national park

Two century-old DC fountains sit decaying and neglected in the woods of a national park in Maryland. The fountains had been missing from the 1940s until they were rediscovered in the woods of Fort Washington National Park in the 1970s.

The top portion of the McMillan fountain, pictured below, was returned to Crispus Attucks park in the Bloomingdale neighborhood in 1983. In 1992 it was moved back to the fenced-off grounds of the McMillan Reservoir just a few blocks away.

The fountain was installed in 1913 at the McMillan Reservoir as a memorial to Senator James McMillan (R – Michigan), who is more remembered locally for his his ambitious McMillan Plan to beautify Washington. The fountain was dismantled in 1941, when the reservoir was fenced off from the public.

Though the top of the McMillan Fountain had been restored to the reservoir grounds, a Bloomingdale ANC commissioner told me the base of the fountain was in the woods in Fort Washington along with the remains of the fountain that stood at the center of the now-razed Truxton Circle.

I went to Fort Washington in search of these discarded works of art. I asked a park ranger where the fountain was and she drew me a map, saying that it stood in the park’s “dump” and partly behind a fence.

I went to the picnic area nearest the site and walked into the woods a short distance where I found a fence. Behind it stood piles of bricks and other discarded building materials.

Beside the site is a dugout that serves as the back court to Battery Emory, a concrete gun battery built in 1898 to protect the capital city from enemy ships.

As I passed through the unfenced dugout, I immediately spotted few granite blocks that served as the cornerstones of the base bowl. Though they are strewn about the ground, a 1912 photograph can help us identify what pieces went where.

The elements of the fountain were stacked like totem pole. The bottom element features carved classical allegorical heads from whose mouths water gushed into the carved bowls below.

Fence material and tree debris cover the carved granite (left) that stood as the fountain base (right).

The next element of the stack is the fluted base to the top bowl.

Several other large granite stones are stacked and marked with numbers, presumably to help in reassembly.

The site also contains the rusting remains of the fountain that stood at Truxton Circle, which formed the intersection of North Capitol Street, Florida Avenue, Lincoln Road, and Q Street. The circle was built around 1901 and the fountain installed there originally stood at the triangle park at Pennsylvania Avenue and M Street in Georgetown.

Truxton Circle stood at Florida Avenue, North Capitol Street, Q Street, and Lincoln Road from 1901 to 1940, when it was demolished to aid commuter traffic.

A newspaper at the time described it as one of the largest fountains in the city. The circle was removed in 1940 to ease the flow of commuter traffic. At that time, the fountain, which may date to as early as the 1880s, made its way to Fort Washington to rust in the woods.

The metal pedestal (left) held up the fountain bowl whose rim rusts in pieces on the ground (right). Notice the classical egg-and-dart pattern.

The fountain was also noted for the metal grates that stood near its base. Now these grates sit rusting in the woods.

If you want to see the fountain remains for yourself at Fort Washington National Park, go to picnic area C. Beyond the end of the parking lot is a restroom building and behind that is the fountain “graveyard.” A fence encloses part of the site, but you can enter through the large gap down the hillside.

Rather than tossing aside our city’s artistic patrimony, we should aim to restore these treasures to the neighborhoods from which they came. Public art is part of what differentiates cherished neighborhoods from unmemorable places.

These works remind us of the accomplishments and civic-mindedness of generations past and urge us to carry on the tradition of civic improvement for generations to come.

Get a rare glimpse of the McMillan Sand Filtration Site

This weekend we got a rare tour of the dormant McMillan Sand Filtration Site just north of Bloomingdale.

The site sits behind locked fences between North Capitol Street, Channing Street NW, 1st Street NW, and Michigan Avenue NW. The filtration site opened in 1905 to purify river water supplied to a burgeoning capital.

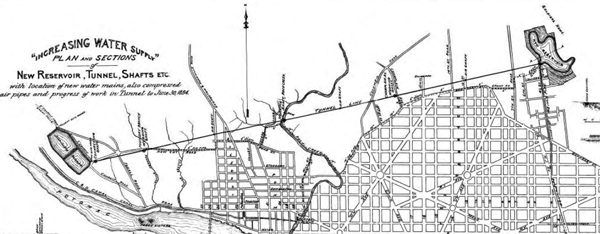

The filtration plant contains 25 acres of underground sand filtration cells. Water flows from the “castle” on McArthur Boulevard NW at the Georgetown Reservoir through an arrow-straight tunnel to the valve house on 4th Street at the McMillan Reservoir.

The reservoir opened in 1902 and is actually a dammed stream valley. Since the reservoir stores untreated river water, the water must be cleaned before it can be distributed to residents’ taps.

At the turn of the 20th century, a debate ensued between proponents of chemical purification and slow sand filtration. Slow sand filtration won the debate and Congress provided money to build the sand filtration cells.

The process of slow sand filtration is pretty simple. Water fills a cell that contains 2 feet of sand at the bottom— it’s like an underground beach.

The water percolates through the sand leaving contaminants behind in the sand. When the water reaches the floor under the sand, it exits the cell and is distributed into the city’s water pipes.

The sand itself required routine cleaning to remove the contiminants. Clean sand was stored in the concrete silos that stand in rows on the site.

Workers replenished the cells by dumping clean sand through the various access holes on the roof of each cell.

In fact, an early photo shows fresh sand dumped into a cell.

Regulator houses contained valves for regulating the flow of water through each cell.

The top of the filtration site was turned into a park, as envisioned by Sen. James McMillan (R – Michigan), famous for his ambitious McMillan Plan to beautify Washington.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., designed the park grounds on top of the sand filtration cells. Since the park closed to public access during World War II, the park’s recreational features, including green lawns, park lamps, walkways, and staircases, sit decaying today.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., designed the park grounds on top of the sand filtration cells. Since the park closed to public access during World War II, the park’s recreational features, including green lawns, park lamps, walkways, and staircases, sit decaying today.

In the 1980s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers build a rapid sand filter on the part of the reservoir west of 1st Street NW, thus obviating the need for the slow sand filters east of 1st Street. The western section today holds the active open-air reservoir and rapid sand filters that supply clean water to much of Washington.

That section, which is still an active reservoir and water treatment plant, is closed to the public. What’s most unfortunate is that the western section contains the most notable feature of the reservoir park.

Shortly after Sen. McMillan’s death, Congress and donors in his home state of Michigan decided to honor the senator with an ornate fountain to adorn the park that bears his name.

The 1912 fountain, designed by Herbert Adams, contains a bronze sculpture of 3 nymphs on a pink granite base. In 1941 the fountain was dismantled, left in storage and mostly neglected until the top portion of the fountain was returned to Crispus Attucks Park in 1983. In 1992 the top section was moved to its current location, at the active reservoir site, locked away from public access.

One can still see the top portion of the fountain by glancing through the fence on 1st Street NW.

The base of the fountain remains somewhere in Fort Washington National Park in Prince George’s County. Perhaps someday the District, the federal government, and neighbors can raise the funds to reunite and restore the fountain for public enjoyment.

McMillan Site gets video tribute

Bloomingdale resident Snorre Wik has produced this video of the shuttered McMillan Sand Filtration Site.

Several months ago the city decided to reset development plans for the site and do part of the preliminary traffic and groundwater studies itself. We will keep you posted as development plans for the site inch along.

Recent Comments