Census data for LeDroit Park

In preparation for redistricting Ward 1’s ANCs, the DC Office of Planning has released block-by-block demographic data for the District. We have combined the data for the blocks that comprise LeDroit Park to create a LeDroit Park census.

Analyzing U.S. Census data for LeDroit Park proves difficult because the of the way census tracts are drawn. Our census tract, 34, combines LeDroit Park and Howard University. Dorms on the northern end of the campus, far away from LeDroit Park, account for 717 of the tract’s 4,347 residents, thus skewing tract data. Furthermore, the tract also inclues several blocks bounded by Rhode Island Avenue NW, Florida Avenue NW, and 2nd Street NW.

Fortunately, the Census Bureau provides data for each block, allowing us to combine the statistics for those blocks in LeDroit Park, while excluding the Howard University campus. In the map below, we have outlined the tract in blue and shaded the blocks for LeDroit Park in red.

View LeDroit Park Census in a larger map

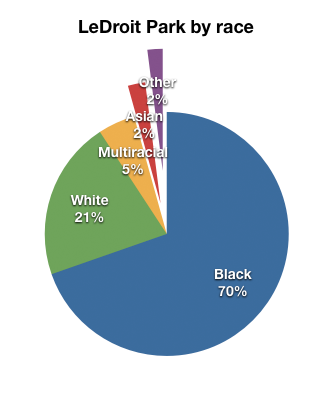

Though LeDroit Park started out as an exclusively white suburban neighborhood, by 1910 the neighborhood was almost entirely black. Today, 100 years later, the neighborhood is 70% black and is continuing to diversify.

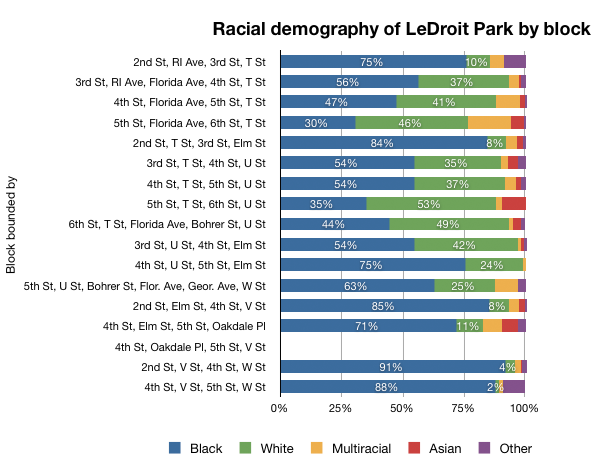

However, when looking at the numbers on a block-by-block basis, you see that the neighborhood demography, must like that of the District itself, is unevenly distributed.

The block bounded by 5th Street, T Street, 6th Street, and U Street is 53% white, the highest in the neighborhood. Likewise, the block containing the Kelly Miller public housing is 91% black, the highest percentage in the neighborhood. The block containing the arch and the Florida Avenue Baptist Church comes closest to black-white equilibrium at 44% and 49% for each group respectively.

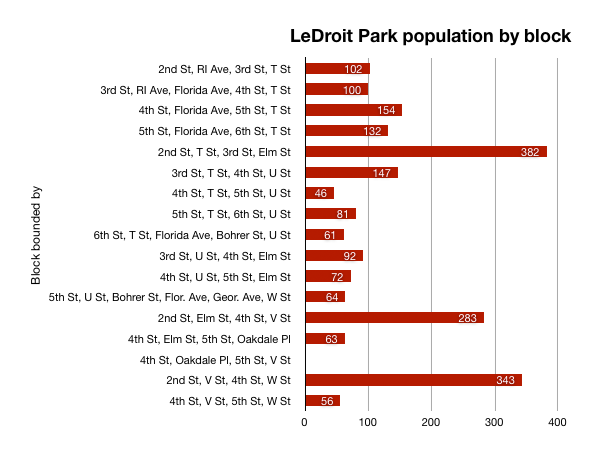

When looking at total population numbers for each block, you see that the two most populous blocks contain Howard University dorms. The block bounded by 2nd Street, T Street, 3rd Street, and Elm Street has 382 residents and contains Slowe Hall, which houses 299 students.

The second most populous block contains the new park. However, it also contains Carver Hall, which itself houses 173 students. Certainly these blocks are big, but the fact that their population numbers are off the chart has more to do with student dorms than with any inherent difference in housing density.

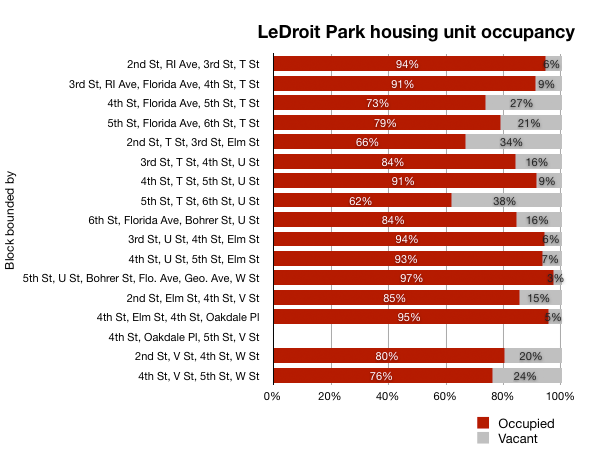

Finally, when we look at housing vacancy, we see that the block bounded by 5th Street, T Street, 6th Street and U Street has 38% of its housing units vacant. We’re not sure what’s causing this number, but we suspect that the apartment building at 5th and U Streets NW boosted the vacancy rate. The building has since been finished and is fully rented.

The block with the second-highest rate of vacancy contains the now-renovated Ledroit Place condo building at 1907 3rd Street NW.

It would be interesting too look at other data, including household income, car ownership, and age distribution for the neighborhood. However, the Office of Planning’s spreadsheet only covered population numbers, racial distribution, and housing unit numbers, so those are the metrics we graphed.

How LeDroit Park Came to be Added to the City

The following is a Washington Times article from 1903. The article explains some of the early history of the neighborhood and even includes three photos, the first of which was misidentified as Fifth Street, though we have actually matched it up with Second Street. We have included a few links to related information.

Second Street opposite the Anna J. Cooper House.

HOW LE DROIT PARK CAME TO BE ADDED TO THE CITY

Washington Times

Sunday, May 31, 1903For Many Years the Section of Washington Known by That Name Had Practically Its Separate Government and Had All the Characteristics of a Country Town, Although Plainly Within the Boundary Limits. * * *

In that portion of Florida Avenue between Seventh Street and Eighth Streets northwest where the street cars of the Seventh Street line and the Ninth Street line pass over the same tracks, thousands of passengers are carried every day, and probably but a few if any realize the fact that they are passing over a road older than the organization of the city, a road that dates back to the Revolutionary period— the Bladensburg Road, which connected Georgetown with Bladensburg before the location of the National Capital was determined.

The Map on the Wall.

If the people passing this point will note the little frame building occupied by a florist, 713 Florida Avenue northwest, they will observe that in front of these premises and fastened to the blacksmith shop adjoining is a goodly sized signboard on which is painted an old map of this section and showing the intersection of the old Blandensburg Road and Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue. From this map it is seen that Seventh Street Road [now Georgia Avenue] intersects Boundary Street and the old Bladensburg Road at a point about 100 feet east of where the two roads join at an acute angle, and glancing along the lines of Boundary Street and the north lines of some buildings which have been erected in this angle we easily see the direction of the Bladensburg Road and discover that the small building 713 Florida Avenue northwest marks the spot where the Bladensburg Road deflected from Boundary Street and bore off in a northeasterly direction toward Bladensburg.

Once Part of Jamaica Vacancy.

The map referred to is said to be a portion of [the estate named] Jamaica and and Smith’s Vacancy, but if we examine the plats in the office of the Surveyor of the District we will hardly find on file any plats of those sections, but may learn that Le Droit Park was once part of Jamaica and Smith’s Vacancy and possibly a portion of [the estate named] Port Royal. Prior to the cession of the territory now included in the District from Maryland the land known as Jamaica was owned by one Philip R. Fendall, of Virginia. He conveyed this tract of 494 acres on the 12th day of January, 1792, to Samuel Blodgett, jr., of Massachusetts, and from this point the title of the land can be traced down to the present time.

The names attached to the different vacancies establish the names of the various owners of lands adjoining Bladensburg Road at the time it was abandoned as a thoroughfare and taken up as a portion of the farms in that section, and the presence of this old road accounts for some of the peculiar lines in some of the northern boundaries of some of the lots in Le Droit Park. This road crossed Second Street at a point north of Elm Street here. The old plats show Moore’s Vacancy. The road finally joined the present road to Bladensburg at a point where the sixth milestone of the norther line of the District was located.

It is probable that this peculiarly natural boundary of some of the lands which afterward became Le Droit Park may have had something to do with the strange lines which are found in the streets of that suburb, although it was not the intention at the time that Le Droit Park was subdivided to have the streets conform with the city streets.

Site of Campbell Hospital.

During the civil war the territory now contained in Le Droit Park was used as the site of Campbell General Hospital, one of the important hospitals near Washington. The hospital comprised some seventeen separate wooden buildings, erected in the form of a hollow square, with the central portion divided into irregular spaces by buildings cutting across the inclosure and connecting the outside buildings.

The larger dimension of this hospital was fro north to south, and extended from Boundary Street, now known as Florida Avenue, on the south, to the land occupied for many years as a baseball park, situated south of Freedman’s Hospital, and designated on some of the old maps as Levi Park. From east to west the hospital covered the ground from Seventh Street to what is now known as Fifth Street in Le Droit Park, and it is possible that a portion of the space between Fifth Street and Fourth Street was also included in the hospital inclosure.

The McClelland Residence.

At this time there were only two dwellings in the tract known afterward as Le Droit Park— the McClelland and Gilman homestands. Each included about ten acres of land used for grazing and garden purposes. The McClelland property and the Gilman property were divided by a row of large oak trees which were situated about fifty feet apart and continued from Florida Avenue, then Boundary Street, to the northern line of the park.

[See the following 1861 map, a map we extolled several months ago:

To the east of the Gilman tract was a narrow strip of land known as the Prather tract. East of this was Moore’s Lane, now Second Street, and still to the east was the tracts of the Moores, George and David, covering the territory as far east as the present location of Lincoln Avenue [now Lincoln Road], on which was located Harewood Hospital, another hospital of considerable note during the civil war.

T.R. Senior, who was commissary at Campbell Hospital, returned to the city some twelve years after the war closed and purchased a residence at the corner of Elm and Second Streets, where he now resides. Members of the family of David McClelland now occupy the old homestead on Second Street.

Following the close of the war it became necessary to provide for such of the freedmen as were in need of assistance. Campbell General Hospital was occupied by the freedmen until August 16, 1869, when the patients were transferred to the new Freedman’s Hospital, which has been erected in connection with Howard University.

The property upon which Freedman’s Hospital stands consisted of a tract of 150 acres and was purchased from John A. Smith. In April, 1867, Howardtown was laid out and soon after some 500 lots were sold, and at this time it seems that the idea was conveyed that streets would be opened to the south through the Miller tract. In April, 1870, the Howard University purchased the Miller tract, and laid out streets to connect the streets of Howardtown with the city streets, and a little later built four houses on the line of what is now known as Fourth Street and in 1872 subdivided the Miller tract, but for some reason the plat was not recorded.

In 1873 the Miller tract was sold by Howard University to A[ndrew] Langdon, and a short time afterward A[mzi] L[orenzo] Barber, formerly secretary of Howard University, became associated with Langdon and hs partner, and by arrangements with D[avid] McClelland, all of the three tracts known as the Miller tract, the McClelland tract, and the Gilman tract were united and subdivided, and in June, 1873, a subdivision known as Le Droit Park was placed on record in the surveyor’s office. A subsequent plat was filed some eighteen months later, in which the proprietors of the subdivision declared it to be their purpose and intention to retain and control the ownership of all the streets platted, and the right to inclose the whole or any portion of the tracts or tract included in the subdivision and to locate and control all entrances and gates to the same.

During the autumn of 1876 A. L. Barber & Co. commenced the erection of fences across the north line of Le Droit Park, and from this time until August, 1891, fences were maintained along the northern line of the park. From 1886 to 1891 frequent fence wars were in operation. The fence across what is now Fourth Street would be removed by one party, and the opposing party would secure an injunction and restore it. This mode of procedure was repeated at various times until in 1901 a compromise verdict was agreed upon by the two factions and the fence was removed, Fourth Street was improved north of the park, and the streets of the park passed into the control of the city after a period of some eighteen years of private ownership.

The organization of Le Droit Park, under the limitations of the plat filed in 1873, was a peculiar experiment, that of the founding of an independent suburb adjoining the city. the southern line of the park was inclosed with a handsome combination iron and wood fence, some of which may now be found on the southern line of the McClelland property. Buildings were erected with plenty of room around them, and during the period from 1873 to 1885 the larger part of the buildings were planned and erected by James H. McGill. Double houses were quite common, but it was not until 1888 that such a thing as a row of houses were known in the park.

Before control of the streets was surrendered to the city the conditions existing in the park resembled closely those found in small country towns. Many of the inhabitants owned cows, which were pastured upon the vacant lots; the women “went a-neighboring,” and the social life savored strongly of a village, and yet it was near the city. The express and telegraph messengers, however, always collected of residents an extra fee for the reason that they lived out of the city.

With the opening of the streets and the introduction of street cars the park soon lost its former characteristics and became part of the city with all of its advantages and disadvantages. The opening of Rhode Island Avenue [from Florida Avenue eastward] spoiled in a measure the former beauty of the McClelland and Gilman homesteads, although there is still much more ground remaining in both of these old tracts that many people would care to own. The opening of Fifth Street will, to some extent, divide the traffic which now finds a way through Fourth Street. Sixth Street ends at Spruce Street [now U Street], and further progress seems barred by the residence, 601 Spruce Street, and there seems no immediate chance of the extension of Third Street above its present limit [at V Street??], where progress is barred by a high fence decorated with the advertisement of a prominent firm.

Former Familiar Street Names.

The old names of the streets of the park, such as Harewood Avenue [now Third Street], Maple Avenue [now U Street], Moore’s Lane [later Le Droit Avenue, then Second Street], Linden Street [now Fourth Street], Larch Street [now Fifth Street], Juniper Street [now Sixth Street], and Bohrer Street [still extant], are nearly forgotten, and have passed away with the fence and its period. The names of the city streets have taken their places, and with the growth of the population the country life and country scenes have given way to those of the city.

What’s That on the Grassy Knoll?

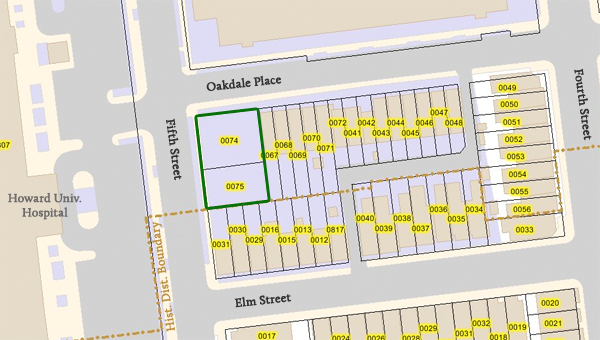

At the corner of Fifth Street and Oakdale Place, at the very edge of the Howard University campus, sits a fenced-in grassy knoll. The site is across the street from the hospital and sits just outside the historic district boundary. About a year ago a sign planted on the site announced the pending arrival of new houses. The sign came down many months ago and nothing much happened. Sure, Howard mowed the lawn, but not much else happened.

On Christmas Eve, Howard University sold the two lots for $250,000 each to Bowie-based Tito Construction Company LLC and just last month DCRA issued building permits for the two lots (#B1000822 & #B1000823). Each permit states the scope of work as

BUILDING A NEW 3-FLOOR WITH A CELLAR 2-UNIT FLAT STRUCTURE.

The lots are much larger than every other lot on the block and these two two-unit houses will likely be spacious.

Snow Mound

Unlike Metro, Howard University Hospital must stay open no matter the weather. As such the groundskeepers are quick to remove snow the moment the first flake hits the ground. The employee parking garage on the block bounded by Fourth Street, V Street, Fifth Street, and Oakdale Place also needs its top level cleared of snow. But where does the snow from the top level go? Well, over the edge it seems.

Monster Plows

Due to the overwhelming amount of snow that has worn down the city’s plows, the District has contracted with a Massachusetts company to help dig us out. This morning we spotted part of the Bay State crew and its heavy construction equipment clearing Fifth and U Streets here in LeDroit Park. The ferocious looking machines are scraping the streets down to the pavement and amassing snow mountains that will take weeks to melt.

Going for a Record

The record snow that accumulated this weekend brought us out to snowball fights and sledding in Meridian Hill Park. With few stores open and few roads passable, Saturday was a true holiday in the old-fashioned sense.

Howard University Hospital’s groundskeeper was out in heartbeat clearing the hospital’s sidewalks while contractors cleared the hospital’s parking lot. Pretty impressive!

Neighbors dug their cars out of snow and the usually busy Florida Avenue carried more pedestrians then automobiles. The District government sent numerous plows along U Street and Florida Avenue, largely neglecting (understandably) the quiet streets of LeDroit Park.

You didn’t need a 4×4 to get around this weather. These two girls found that a daddy-powered sled was the most convenient form of transportation.

In Dupont Circle, hundreds of people gathered for a snowball fight. We caught the end of it:

Is a white Hummer camouflaged when it’s in the snow? These snowballers were able to spot and pelt it.

This Suburban sped away as soon as the light turned green.

For cars in LeDroit Park, Fourth and Fifth Streets are passable, but the east-west streets are better left to the four-wheel-drives.

More snow is expected Tuesday night and during the day on Wednesday. Were Pres. William McKinley still alive today, he would not only argue the merits of a gold standard with Rep. Ron Paul, but would also scoff at this relative “dusting”. Though we’ve recorded 45 inches so far this winter, the winter of 1898-99, during McKinley’s administration, set the city’s record, dumping a total of 54.4 inches on the capital!

If you’re tired of the snow, be glad you don’t live in Québec City, which suffers 124 inches of snow each winter… on average!

Eye in the Sky (1988 – 2009)

What a difference twenty-one years make. Below are two satellite photos of LeDroit Park— one taken in 1988 and the other taken in 2009. Toggle back and forth between the two to see how the neighborhood’s footprint has changed.

There are a few noticeable changes:

- Howard University Hospital built an annex behind the main hospital building.

- The entire block bounded by Fourth Street, Fifth Street, V Street, and Oakdale Place is now a multi-level parking garage.

- In 1988, the 500 block of U Street looked gap-toothed; new houses have since been built to fill out the entire north side of the street.

- Street intersections have been replaced with concrete while the roadways remain asphalt.

- The tree canopy is much more expansive now (or the 1988 photo was taken in the winter).

- Houses have been built on the once-vacant land around the northeast corner of Fourth and U Streets.

- The intersection of T Street, Sixth Street, and Florida Avenue has been reconfigured, making way for the pocket park home to the LeDroit Park entrance arch.

- The Schoolhouse Lofts condo building has since been built at Second and V Streets.

Did we miss anything?

Old Street Names

Careful observers occasionally spot the old street signs adorning a few of the light poles in LeDroit Park. When the neighborhood was originally planned, most of the streets were named after trees. LeDroit Park’s street system didn’t fit with the L’Enfant Plan in either name or alignment—much to the dismay of the District commissioners—and the street names were eventually changed to fit the naming and numbering system.

A perusal of old maps reveals that the street names changed over time, not all at once. Elm Street is the only street that has retained its name. Since your author lives on Elm Street he has learned to respond to puzzled faces that know that Elm doesn’t fit the street naming system: “It’s kinda like U-and-1/3 Street”.

Anna J. Cooper Circle didn’t have a name at all until 1983, when it was restored to its circular form after a decades-long bisection by Third Street.

Just outside of LeDroit Park, the city renamed a few streets as well: 7th Street Road became Georgia Avenue and Boundary Street, the boundary of the L’Enfant Plan, became Florida Avenue.

Here is a table matching the current street names with their previous names.

| Old Name | Current Name |

| Le Droit Avenue | 2nd Street |

| Harewood Avenue | 3rd Street |

| Linden Street | 4th Street* |

| Larch Street | 5th Street |

| Juniper Street | 6th Street |

| Elm Street | (same) |

| Boundary Street | Florida Avenue** |

| 7th Street Road | Georgia Avenue** |

| Oak Court | Oakdale Place |

| Maple Avenue | T Street |

| Spruce Street | U Street |

| Wilson Street | V Street** |

| Pomeroy Street | W Street** |

| (unnamed before 1983) | Anna J. Cooper Circle |

| * For a short period, 4th Street was called 4½ Street. ** Though these streets were just outside the original LeDroit Park, we have included them for reference. |

|

Signs bearing the old street names have reappeared in the neighborhood, and according to the Afro-American, were put up in 1976: “The LeDroit Park Historic District Project was instrumental in getting the D.C. Department of Transportation to put up the old original street names for this Historic District Area under the present street name signs”.1

Unfortunately, some of the signs are showing their 33 years of weather, as this sign at Third and U Streets shows.

Eventually these signs will have to be replaced, but rather than placing the old names onto modern signs using a modern typeface, we suggest something that evokes the history without being mistaken for the current street name:

White text on a brown background is the standard for street and highway signs pointing to areas of recreation or cultural interest. Seattle started using the color scheme to mark its historic Olmsted boulevards and New York has long used the combination for street signs in its historic districts. The adoption of this style of sign would alert visitors and residents to the neighborhood’s historic identity while the different color and typeface would prevent confusion with the actual street names (U St NW in this case). Typographers would be pleased by the use of Big Caslon Medium, a serif typeface based on the centuries-old Caslon typeface.

- Hall, Ruth C. “Historic Project”. Washington Afro-American. 1 May 1976.

U Street in 1908

In our casual search of LeDroit Park’s history, we occasionally come across interesting tidbits in the most unexpected places.

A 1908 issue of The World To-Day, a self-described “monthly record of human progress”, featured an article on the breadth of professions and positions held by blacks in Washington at the time. The article featured a photo of the U Street, looking east from 5th Street. We have provided the original photo as well as a photo taken in the same perspective last week.

Ever since air conditioning, window shutters have never been as popular as they used to be.

Recent Comments