Where Have All the Craftsmen Gone?

DC development blog DCmud interviewed Grant Epstein, who recently withdrew his proposal for 1922 Third Street NW. Mr. Epstein’s development company focuses primarily on adaptive reuse of historic properties.

One part of the interview caught our eye, as Mr. Epstein confirms what we have long suspected: ornate houses are difficult to build today because it’s harder to find skilled craftsmen to built custom ornaments:

It’s amazing the amount of craftsmanship that went into these houses on [Capitol Hill]. Detail that it’s very hard to replicate today. So the old townhouses, they inspire me. We’ve lost a lot in our new buildings, in the construction of them. It primarily has to do with the number of pieces that go into a house. There aren’t many craftsmen that know how to do the details.

….

[T]he people don’t exist anymore… the trades don’t exist. For instance, iron staircases. Two or three guys in the area do iron staircases the right way. Two or three guys! Back in the early 1900s there were forty! It’s a big difference. At M Street we found the iron treads from an old turn of the century house and recast the iron posts in order to use the same style that was supposed to be there, but was missing. There were only a couple of guys who knew how to do that.

While walking around LeDroit Park, we frequently notice detailed architectural ornaments that never adorn contemporary buildings. How many bricklayers today have the experience and skill to lay bricks as was done at the Mary Church Terrell house when it was built?

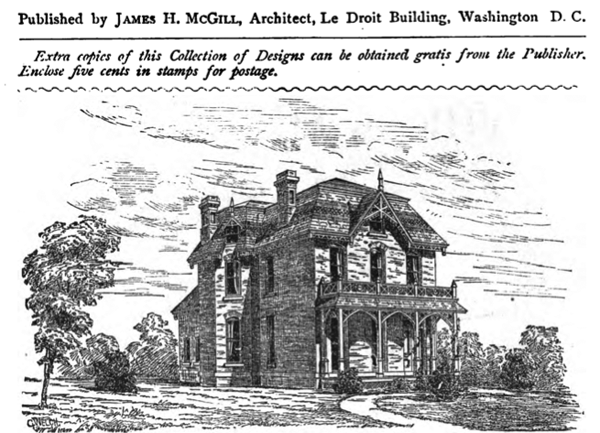

And how many bricklayers have the experience to construct a façade like this one on the McGill carriagehouse at 1922 Third Street?

The owners of this house on Third Street told me how impossible it was to find somebody to replicate these columns:

Rarely will you find anything like the gingerbread on the Anna J. Cooper house:

Brackets like these require a good amount of craftsmanship to carve and paint:

Contrast these houses with the vacant apartment house at 1907 Third Street NW:

Heritage Trail for LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale

You’ve seen them around DC. Those tall signs with historic photos and narratives explaining what happened in that neighborhood 70 or 200 years ago. Several neighborhoods in DC have heritage trails, courtesy of Cultural Tourism DC.

We in LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale are on our way to getting our very own heritage trail, but the LeDroit Park-Bloomingdale Heritage Trail Working Group needs your help.

The Working Group will meet on Wednesday, May 12 at 7 pm at St. George’s Episcopal Church (Second & U Streets) to collect stories, old photos, and to plan how to interview our neighborhoods’ long-time residents.

Do you have an old photo or an old story to tell or are you interested in local history? LeDroit Park has hosted many notable residents from Civil War generals, to Duke Ellington, to Walter Washington, and even Jesse Jackson!

Come join us Wednesday night and learn how you can help.

Wednesday, May 12

7 pm

St. George’s Episcopal Church

Second & U Streets NW

1922 Withdrawn

Community Three Development withdrew its application for 1922 Third Street. As we wrote before, the developer proposed renovating and expanding the historic main house, renovating the historic carriage house, and constructing a new townhouse on the south side of the lot.

The proposal was set to go before the Historic Preservation Review Board last Thursday, but the developer, while at the meeting, withdrew his proposal and the board ended discussion on it.

In preparation for the board meeting, the Historic Preservation Office issued this staff report critiquing the proposal from a historic preservation standpoint. One of the most significant suggestions was that the developer remove the “hyphen” section connecting the main house with the proposed townhouse, a concept alteration that would require a zoning variance. Receiving a zoning variance is by design a costly and protracted process that’s not guaranteed to succeed.

In an email to us, the developer stated that due to these various issues, ranging from some neighborhood opposition to unresolved zoning issues, they could not proceed with their plan.

Regarding the politics of the proposal, the developer wrote:

[T]he economic and physical constraints inherent in the redevelopment of this site require all participants to contribute to a solution that benefits the greater whole, and in this case, we unfortunately found that certain stakeholders were unwilling to do so. We will potentially revisit this project when local pressures realign, but it may be very difficult for progress while these differences remain irreconcilable.

Through this process, we were surprised to the degree to which the developer reduced his ambitions, but ultimately the business of housing is a business driven by public tastes, local regulation, construction methods, and— above all— economics. If a proposal is financially impractical, it will not get built, unless it is built at a loss as a pet project of a wealthy financier.

Somebody will eventually buy the house, though maybe not soon. For it to remain a single-family house, as many want it, a potential owner must be able to afford replacing the roof, gutting the interior, building a new kitchen and bathrooms, replacing the wiring, replacing the plumbing, installing insulation, replacing many of the floors, installing a new furnace, replacing much of the drywall, fixing the foundation, and repairing the carriage house— renovations that will likely run near a million dollars, if not more, on top of the sale price.

A condo project with fewer units (and without a townhouse) could still succeed, but the reduced number of units will likely exclude an affordable housing component (only required of projects with 10 or more units). Furthermore, those fewer units will have to be sold at higher prices to justify the renovation costs.

The neighborhood opposition (far from universal, mind you) unwittingly set a new entry criterion for purchasing the property: if you want to live at 1922 Third Street, you must be a very wealthy person.

* * *

What do you think? Are you glad or are you disappointed that the proposal was withdrawn?

McGill Carriage House Reimagined

In the last round of concept changes for 1922 Third Street, the developer proposed restoring an old wall (pictured above) attached to the carriage house. The developer added it after we discovered an 1880 architectural pattern book produced by James McGill, the architect of LeDroit Park’s original and eclectic houses.

Google, in its effort to scan and publish old, public-domain documents, scanned the pattern book and posted it online. You will notice engravings of several other houses that still stand in LeDroit Park today.

We have recreated a 3D model of the carriage house based on James McGill’s original design. We had to guess the colors since the McGill publication was printed as a simple black-and-white engraving. Download the Google SketchUp file (get SketchUp for free to view it) or watch the video tour below.

Unlike today’s garages, these carriage houses were designed to house a carriage or two, several horses, and bales of hay. Modern cars, once fondly called “horseless carriages”, obviate need for these equine accouterments and the developer wishes to convert the carriage house into living quarters.

The problem is that the zoning code is more accepting of car housing than of people housing; converting an old carriage house into living quarters will require a zoning variance. Whatever gets built at the site, be it through this developer or another, would ideally include the restoration of the carriage house and its adaptation from housing for horses into housing for people.

* * *

The design for 1922 Third Street will go before the Historic Preservation Review Board on Thursday. Interested parties may comment on the proposal either way at the hearing.

Historic Preservation Review Board – Thursday, April 22 at 10 am at One Judiciary Square (441 Fourth Street NW), Room 220 South. Read the public notice

1922 Third Street Revised

On Thursday ANC1B will vote on the revised proposal for 1922 Third Street. The new proposal, pictured above, modifies the scale of the proposed new townhouse (on the left). This part of the project was by far the most controversial, as the previous design (its outline dotted above) called for structure taller and much deeper than the adjacent townhouses.

In fact this revised concept reduces the townhouse size significantly compared to the original concept (dotted below). Another nice feature is the articulation added to the side of the townhouse. Two bays extend out from the side, as does an ornate chimney, much like others in the neighborhood.

These elements combine to produce a structure less visible from the north side of the property on U Street. The developer has shortened the rear addition to allow the historic carriage house to stand out more on its own. The addition’s architectural style resembles that of the main house more closely than the previous design, which combined elements of both the main house and the carriage house.

The developer explained the changes in his own words:

We reduced the size, footprint, height, of the townhouse portion of the plan to address concerns about the mass of this portion in the original concept. The height of the townhouse has been reduced to match the height of the neighboring property and is now below the height of the main structure. The depth of this portion has also been reduced by approximately 30 feet. Further, the profile has been revised to step down towards the rear of the site to increase light to adjacent areas. The result of these combined actions have reduced the mass of the building by almost 40% and a mass of building that is drastically smaller than what would be allowed by-right on the adjoining parcels to the south.In addition to the reduced massing, we eliminated 2 units in the townhouse portion, thereby reducing the overall number of units from 14 to 12 total units.

The reduced number of units, with the provision of 4 parking spaces, has allowed for an increased parking ratio that is in line with other residential uses in the R-4 zone. This new ratio now eliminates the need for a historical parking waiver.

We have articulated the side of the townhouse portion to be more compatible with the surrounding urban character and to give more visual interest to the side elevation.

The addition to the main structure has been redesigned to be more compatible with the character of the existing building. In addition, this revision has allowed for greater views of the historic carriage house from all angles.

We have also learned that the current front porch of the existing building is not historically accurate and we have subsequently redesigned this element to more closely resemble the historic structure’s original porch.

Indeed the current front porch (first image below) is inconsistent with James H. McGill’s original design published in 1880 (second image below).

The developer will present this revision concept to the ANC on Thursday night at 7 pm on the second floor of the Reeves Building at 14th and U Streets. After the developer’s presentation, the commission will allow the public to ask questions (you can always frame your comment in the form of a question) and will then vote to support or to oppose the project. The ANC will forward its opinion to the Historic Preservation Review Board, which will hold a hearing on this revised concept on Thursday, April 22 at 10 am at One Judiciary Square (441 Fourth Street NW), Room 220 South.

LeDroit Park c. 1941

A few months ago we found this old photo at the Washingtoniana Division of the MLK Library. The photo is an aerial view looking westward on the north end of LeDroit Park. Griffith Stadium, now the site of Howard University Hospital, rests in the background; the stadium was demolished in 1965. To its right (north) is the location to which the Freedman’s Hospital moved in 1869. One will also notice that rowhouses stood on what is now the Gage-Eckington site. Looking closely between V and W Streets, one will see that the Kelly Miller public housing apartments appear to be under construction, dating this photo to around 1941.

(If you’d like to zoom on the photo below, download it as a PDF)

We also found a Washington Senators fan site with a 1960 photo of the stadium in the midst of a game.

Old Maps: The Map that Saved the Capital (1859-1861)

This is the second in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park. Read the first post, The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859).

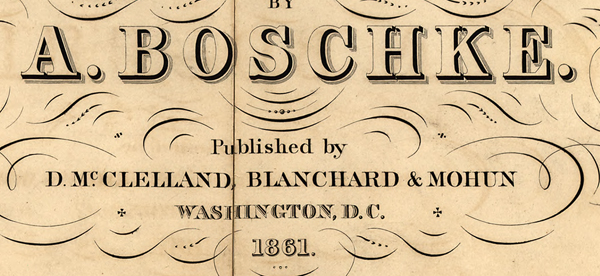

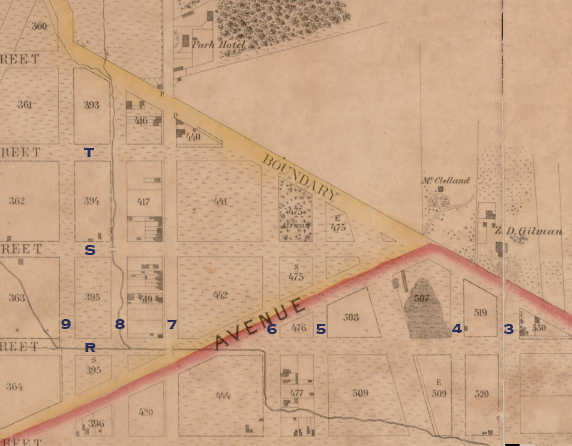

Just a few years after German cartographer Albert Boschke finished his detailed map of Washington City, he completed a map covering the entire District of Columbia. The 1861 map depicts the area around what is now LeDroit Park to be the properties of C. Miller, D. McClelland, and Z. D. Gilman. The original advertisement for LeDroit Park, entitled Le Droit Park Illustrated, also mentions the inclusion of the Prather property, which is not labeled on the map.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Interestingly enough, David McClelland, an engraver, is listed as one of the publishers of the map, so we can assume that he ensured the accuracy of the parcels around his home in what was to become LeDroit Park.

Mr. McClelland continued to live at 301 Boundary Street long after LeDroit Park began to sprout up around him. In fact, Mr. McClelland sold part of his property to form the neighborhood and James H. McGill, architect of LeDroit Park, designed his home, which stood where the United Planning Organization (the old Safeway) now stands.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Mr. McClelland possessed the most accurate map of the nation’s capital. In the hands of the Confederate Army, it could provide a detailed plan for marching on the capital city. In the hands of the Union Army, it could provide a detailed plan for fortifying the capital city. Mr. McClelland knew the value of what he had and unsuccessfully tried to sell it to the War Department, which got a hold of it anyway.

A National Geographic article from 1894 recounts the history of the Boschke map and trouble it caused Mr. McClelland:

At the outbreak of the [Civil W]ar the United States had no topographic map of the District, the only topographic map existing being the manuscript produced by Boschke. He sold his interest in it to Messrs Blagden, Sweeney, and McClelland. Mr McClelland is an engraver, now seventy-four years old, living in Le Droit park. He engraved the Boschke map, which was executed in two plates. With his partners, he agreed to sell the manuscript and plates to the Government for $20,000. Secretary of War [Edwin] Stanton, not apparently understanding the labor expense of a topographic map, thought that $500 was a large sum. There was, therefore, a disagreement as to price. After some negotiations, Mr McClelland and his partners offered all the material, copper-plates and manuscript, to the Government for $4,000, on condition that the plates, with the copyright, should be returned to them at the close of the war. This offer also was refused. There then appeared at Mr McClelland’s house in Le Droit park a lieutenant, with a squad of soldiers and an order from the Secretary of War to seize all the material relating to this map. Mr McClelland accordingly loaded all the material into his own wagon and, escorted by a file of soldiers on either side, drove to the War Department [next to the White House] and left the material.

The Committee on War Claims compensated Mr. McClelland in the amount of $8,500 and never returned the maps.

To the northeast of the McClelland estate sat the narrow pasture of Mr. George Moore, from whose house all the way west to Georgia Avenue (then Seventh Street Road) stood a large grove of trees. Today the grove is covered by the south end of the Howard campus and by Howard University Hospital. In late August and early September of 1861, however, the grove served as a camp for the First New York Cavalry. Lieutenant William H. Beach recounted in his memoirs his stay at the Moore farm:

[T]he companies formed and took up their march … to a part of the city now known as Le Droit Park. This section now well built up was then open country the farm of Mr. Moore. In a grove of scattering scrub oaks near the present intersection of Fourth and Wilson [now V] streets the camp was established and named Camp Meigs.

….

Mr. and Mrs. Moore and their two daughters, with two or three colored servants, were well-to-do and hospitable people of Union sympathies. Some of the officers messed in the house and a few averse to living in a tent had rooms here. On a recent visit the writer found Mrs. Moore still living, about eighty five years of age, and her two daughters with her. Her mind was clear, and her memory of the officers and some of the men very accurate, and not unkind, although there were at that time many things that were annoying to the family.

Next: The Civil War ends and Howard University is established with land that a trustee, Amzi Barber, sells to… himself.

More Details on 1922 Third Street

At Thursday’s monthly meeting of ANC1B, Grant Epstein, president of Capitol Hill-based Community Three Development, presented his proposal for 1922 Third Street, a project we wrote about a few days ago.

His proposal calls for renovating the main house (top right) and carriage house (bottom right) and for constructing a connecting section as well as a new townhouse. Because the lot is 13,600 square feet, the R-4 zoning code permits multi-unit apartments with the maximum number of units set to the lot area divided by 900. Although Mr. Epstein proposes 14 units, the zoning code actually permits 15 units by right (13,600 / 900 = 15.1).

Since LeDroit Park is a historic district, most exterior renovations and all new construction within the district’s boundaries must undergo a review process that begins with the Historic Preservation Office (HPO), which is tasked with ensuring that such projects preserve, match, or enhance the historic character of the neighborhood. Ay, there’s the rub: historic character means different things to different people.

Even if the standards for historic preservation are themselves nebulous, the process itself is designed with a good deal of transparency. Mr. Epstein’s proposal must be approved by the city’s Historic Preservation Review Board, which holds a public hearing during which the applicant presents the plan, the HPO staff present their report, and ANC representatives, community groups, and interested citizens may testify either way on the plan. The board then approves the project, rejects it, or approves it with conditions.

Mr. Epstein stated that he has consulted with HPO staff to refine his proposal to satisfy their interpretation of historic preservation suitable for LeDroit Park. We say “their interpretation” not to be snarky, but rather to remind readers that what constitutes historically appropriate is often a subjective matter of taste and judgment. The past, much like the present, is a collection of different stories, styles, and attitudes. Sometimes there is no one right answer in preservation matters, especially in a neighborhood featuring the Victorian, Queen Anne, Italianate, Second Empire, Gothic Revival, and Spanish Colonial styles among others.

At the ANC meeting and in discussions with residents, we have gleaned the following concerns in addition to many thumbs-up.

1922 Third Street concept, east face on Third Street

Height

Commissioner Myla Moss (ANC1B01 – LeDroit Park), expressed concern that the proposed townhouse (the middle building in the drawing above) was too tall for the row of neighboring townhouses. Mr. Epstein replied that the added height of the building was in fact the suggestion of HPO staff. Their reasoning, Mr. Espstein stated, is that in Washington, end-unit rowhouses have typically been more prominent than the intervening houses. The prominence was typically marked by extra size, extra height, and extra ornamentation. The added height, Mr. Epstein asserted, is in keeping with an end-unit rowhouse. He also noted that many other buildings on the street are taller than what he proposes.

1922 Third Street concept, north face on U Street

Parking

Others expressed concern that the addition of 14 homes on the site would overwhelm the adjacent streets with parked cars since the proposal includes only four parking spaces (one in the carriage house and three in the new adjacent structure pictured above). Mr. Epstein replied that he originally proposed five spaces, but HPO staff suggested that he reduce the number to four so as not to overwhelm a historic structure with an abundance of car parking. Since fewer people owned cars back then, historic architecture is less car-obsessed than today’s buildings— notice how few driveways and garages you’ll find in Georgetown compared to any neighborhood built in the last 60 years.

Mr. Epstein stated that a way to discourage new residents from owning cars was to reduce the amount of available on-site parking. There was at least one skeptical guffaw from the audience, though the reality will likely depend on a variety of factors. Mr. Epstein suspects the project will attract residents more inclined to live car-less.

Commissioner Thomas Smith (ANC1B09), an architect, asked what features besides reduced on-site parking Mr. Epstein would incorporate to discourage car ownership. Mr. Epstein had none, but was open to considering bike storage and car-sharing.

Use

One resident expressed concern that converting what was once a single-family house (before it became a rooming house in the 1970s) into a multi-unit condo building could itself contradict LeDroit Park’s original intent as a country suburb of single-family homes.

Other Details

In response to our question, Mr. Epstein stated that he intended to follow the city’s new inclusionary zoning regulations, which would translate to one of the fourteen units being set aside for a buyer of modest means.

We also noted to Mr. Epstein that though the rowhouse is intended to be an ornamental end-unit— an “exclamation mark” at the end of a row, as he put it— the side of the townhouse, as illustrated in his drawing above, lacks the adornment typical of end-unit rowhouses. Mr. Epstein stated that there was some debate on the issue, still unresolved, as to whether the side of the rowhouse should fully serve as the “exclamation mark” or serve as “canvas” upon which to view the original 1880s structure.

Mr. Epstein also explained the dire condition of the house and carriage house. The main house was entirely gutted of its original interior and years of neglect have left a damaged foundation and ample mold. The carriage house (pictured at the top of this post) is itself crumbling from the weight of the recent replacement roof. Both structures require a significant investment of money to rehabilitate. The investment of money required as well as the uncertain historic review process both make the project something that Mr. Epstein says few developers would touch.

* * *

As a tactical measure to postpone the HPRB’s review of the proposal, the ANC voted to oppose the concept until the developer could present his proposal to the LeDroit Park Civic Association and the ANC’s newly formed design review committee. The ANC will likely address the matter again at the April meeting.

If you’re interested in learning more about the proposal or expressing your concerns or support, feel free to attend any of the following meetings:

- ANC1B Design Committee – Tuesday, March 16 at 6:30 pm at 733 Euclid Street NW.

- LeDroit Park Civic Association – Tuesday, March 23 at 7 pm at the Florida Avenue Baptist Church, 6th & Bohrer Streets.

- ANC1B – Thursday, April 1 at 7 pm on the second floor of the Reeves Building, 14th & U Streets.

Activity at 1922 Third Street

The house at 1922 Third Street (Third and U Streets) is one of the LeDroit Park’s gems and is about to receive some much needed attention. At Thursday’s ANC1B meeting, Community Three Development will submit this concept to renovate the main house, to renovate the carriage house, and to build a new townhouse at the southern edge of the property.

The house at 1922 Third Street (Third and U Streets) is one of the LeDroit Park’s gems and is about to receive some much needed attention. At Thursday’s ANC1B meeting, Community Three Development will submit this concept to renovate the main house, to renovate the carriage house, and to build a new townhouse at the southern edge of the property.

The developer recently finished the swanky M Street Flats located in Mount Vernon Triangle area. The group also completed The Nine on the 1300 block of Ninth Street, backing up to the historic Naylor Court. If these forerunners are any indication, 1922 Third Street may receive a high-end renovation.

The developer’s design, in his words,

creates an addition to the existing main building that is smaller in scale and secondary to the main building, allowing the main structure to continue to read as the dominant form on the site. This addition terminates in a “carriage house court,” designed to celebrate the existing carriage house, while maintaining the historic structure’s existing view corridor from U Street. A new unsubdivided townhouse lot and structure is created to terminate the row of townhouses directly to the south of the site. The result of these interventions preserves and enhances the character and urban form associated with the main structure and corresponding carriage house.

Though Community Three will need the approval of the city’s Historic Preservation Review Board for the overall project, they are not seek zoning variances.

The proposal calls for 14,000 gross square feet of space and features 14 residential units and four garage spaces— a mixture that the developer claims zoning ordinances permit.

Here are some drawings and diagrams from the concept. Note that the developer proposes to add a new rowhouse on the south side of the property (middle-left of the first drawing)

1922 Third Street concept, east face on Third Street

In the next drawing, the concept preserves the historic carriage house (on the right) and connects it with the main house with a new structure (middle) with a hipped roof that mimics the former and dormers that mimic the latter.

1922 Third Street concept, north face on U Street

With the new connecting building and rowhouse the project will increase the building footprint on the lot.

1922 Third Street concept, footprint

What do you think of the concept? Leave your questions and comments below and we will try to ask the developer any unanswered questions at Thursday’s ANC1B meeting.

Old Maps: The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859)

This is the first in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park.

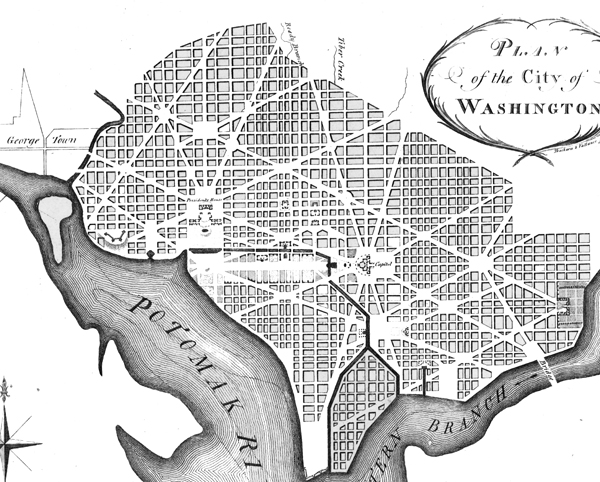

When the Federal Government established the national capital, it was to be located within a 100-square-mile diamond straddling both sides of the Potomac. In fact, the City of Washington was just one of several established cities and settlements in the nascent Federal District, later called the District of Columbia. The City of Washington, as defined by Congress and Peter L’Enfant’s plan, was bounded by the Potomac River and Rock Creek to the west, the Anacostia River to the south and east, and by Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue) to the north. LeDroit Park sits just north of Florida Avenue, in what was originally the rural Washington County, District of Columbia. The District also included the City of Georgetown, the City of Alexandria, and Alexandria County (now Arlington County, Virginia).

The map below, dating from 1792, was the first printed version of the L’Enfant Plan (as amended by Andrew Ellicott) for the City of Washington. Notice that its northern boundary coincides with what is now Florida Avenue. LeDroit Park now sits just to the west of what is marked as “Tiber Creek”. The creek, also called Goose Creek before the founding of the city, originally ran between First and Second Streets NW through Bloomingdale all the way to what is now Constitution Avenue NW, and westward toward the Washington Monument grounds, where it emptied into the Potomac River. Much of the creek is now buried in pipes beneath the city.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

(We have a reliable method of identifying the future LeDroit Park on old maps of Washington: look for New Jersey Avenue NW, which runs diagonally to the northwest from the Capitol. Directly north of where it ends at the city’s border is where LeDroit Park would later be built.)

The capital city grew slowly over the coming decades with new residents, including government workers and Members of Congress, housed in newly constructed houses and boarding houses near the White House and Capitol, respectively. The difficulty in finding enough skilled labor to build a capital city required the leasing of slaves, who were instrumental in constructing many of the grand public buildings that stand today.

It would be a mistake to look at the map above and assume that all the new streets and canals were built together. In fact, the L’Enfant Plan was just that, a plan. The grand, spacious avenues required the clearing of trees and brush after a tedious survey to match the ground with the map.

In fact, by 1842 so much of the city was incomplete that a visiting Charles Dickens belittled Washington as a “city of magnificent intentions” marked by

spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.

Whereas the global financial markets of today allow developers to develop large tracts of land at once, 19th-century cities had to be built piecemeal with speculation limited to small projects. LeDroit Park was no different: only several houses and only a few streets were built at first with the rest to come later.

From 1856 to 1859, German cartographer Albert Boschke charted the District hoping to sell his maps to the U.S. Government. His 1859 map of the City of Washington (below) provided illustrative evidence supporting Charles Dickens’s sneer. Much of Washington, especially its northern reaches near what was to become LeDroit Park, sat undeveloped with only a few cleared streets.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

The only clear north-south street was Seventh Street, which connected the city with the rural county and stretched into Maryland (albeit under different names). At R Street— if one could call it a street— it crossed an open creek that ran through the right-of-way.

Seventh Street’s primacy as the main north-south thoroughfare actually contradicts the intention of the L’Enfant Plan, whose Baroque determination to provide a “reciprocity of sight“, plotted Eighth Street, not Seventh Street, as the more important axis. In fact to this day the right-of-way of Eighth Street is fifteen feet wider than those of Seventh and Ninth Streets, even though Eight carries only a fraction of the traffic burden that the parallel streets carry.

It is difficult to enforce one artistic vision on a democracy; the shifting of axes, from Eighth to Seventh, merely reflects the fact that cities are shaped by their inhabitants in ways the founders never anticipate. The future LeDroit Park was no different.

Next: Alfred Boschke maps the entire District and a future LeDroit Park resident prints it, only to have it seized at gunpoint.

Recent Comments