LeDroit house enjoys an unmatched view

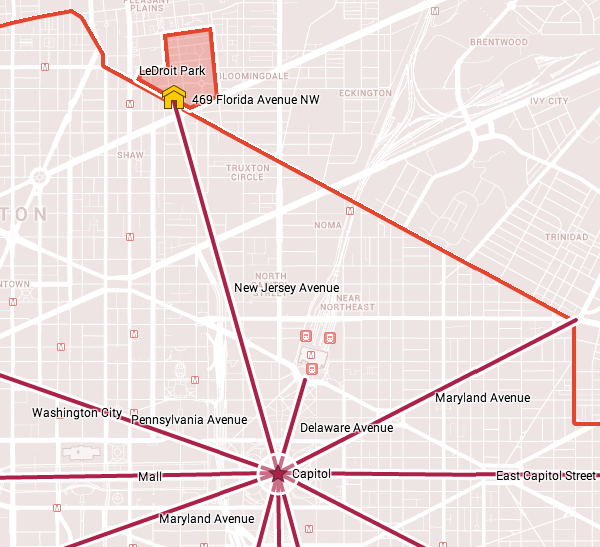

A recent open house in LeDroit Park perfectly illustrated a great feature of the L’Enfant Plan. The house at 469 Florida Avenue sits directly on the New Jersey Avenue view corridor of the Capitol. Typically this location would be reserved for a civic monument such as a statue, circle, square, or government building, but L’Enfant drew his capital within the confines of Florida Avenue, the two rivers, and Rock Creek.

In some cases, such as Rhode Island, New York, and Maryland Avenues in Northeast, Massachusetts and Connecticut Avenues in Northwest, East Capitol Street, and Pennsylvania Avenue SE, subsequent city officials and developers continued these avenues beyond the city’s original boundary.

LeDroit Park, however, stood right in the way of what could have been an extended New Jersey Avenue NW. Instead of terminating the avenue at a civic point, builders in the neighborhood’s rowhouse era (1880s and after), built without regard to the design principles of the L’Enfant Plan. The result is that one row house has a stunning Capitol view worthy of a monument.

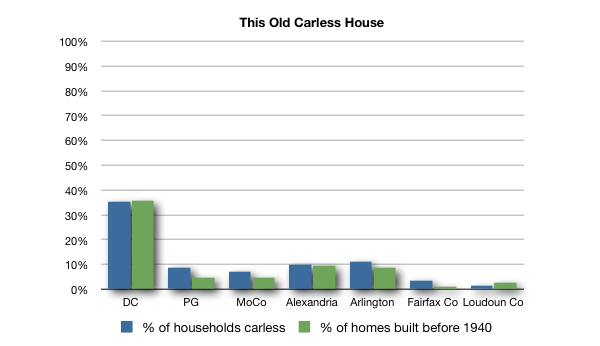

Carless in LeDroit

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Among the nicest features of LeDroit Park are its walkability and its proximity to downtown. We can bike downtown to work in 15 minutes, or if it’s raining, take the bus or the metro and be there in 25 minutes. The restaurants, shops, and bars along U Street are only a short walk away.

The notion that it is easy to live in LeDroit Park without a car consistently confounds many suburbanites, but our variety of transportation options is no accident.

Our neighborhood is just outside the original L’Enfant city. In L’Enfant’s time, the main form of transportation was the human foot, so a city designed from scratch, like Washington, had to be relatively flat, like Washington, and compact, like Washington. Horse-drawn streetcars made commuting across the city easier, and electric streetcars eased the daily climb to neighborhoods like Columbia Heights and Mount Pleasant.

After World War II, housing construction exploded, particularly suburban housing construction. The suburban housing model was— and, for the most part, still is— based on several main principles, most significantly, the uniformity of housing sizes (usually large) and the separation of residential and commercial uses. Both larger lots and the separation of uses create longer distances between any two points, requiring a greater effort to go between home, work, and the grocery store.

These longer distances between daily destinations made walking impractical and the lower population densities made public transit financially unsustainable. The only solution was the private automobile, which, coincidentally, benefited from massive government subsidies in the form of highway building and a subsidized oil infrastructure and industry.

LeDroit Park was founded in 1873 and the first wave of single-family and duplex houses designed by James McGill soon followed. The second housing wave brought rowhouses to LeDroit Park, but most of the neighborhood was finished in the early twentieth century long before the dominance of the automobile.

Notice this 1908 photo of the 400 block of U Street in LeDroit Park. You’ll see four people, but only one car.

It’s no coincidence that our neighborhood’s founding, long before the automobile age, relates to its walkability and abundance of transit options. In fact, when we look at the regional Census data, we find a strong relationship between the age of the housing stock and the rate of households without a car.

The only other factor that might influence the rate of carlessness is income, but the closeness of the carless rate and the pre-war housing stock rate is too glaring to ignore. There are plenty of middle-class people in Washington who choose to forgo a private car and the age of the neighborhood may be a strong indication of just how easy it is to live without a car.

Old Maps: The District Before LeDroit Park (1792 – 1859)

This is the first in a series of posts about historic maps of LeDroit Park.

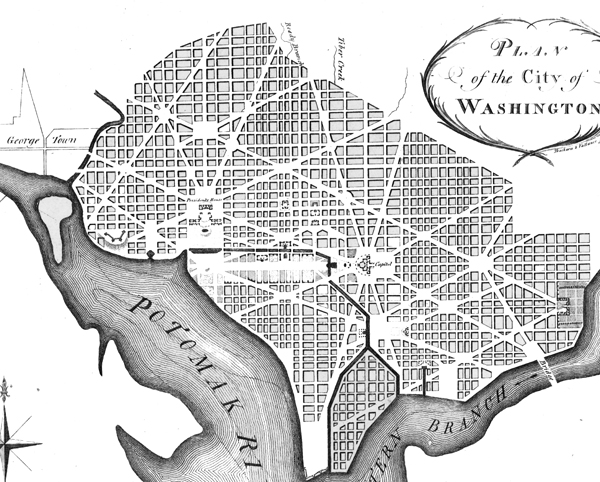

When the Federal Government established the national capital, it was to be located within a 100-square-mile diamond straddling both sides of the Potomac. In fact, the City of Washington was just one of several established cities and settlements in the nascent Federal District, later called the District of Columbia. The City of Washington, as defined by Congress and Peter L’Enfant’s plan, was bounded by the Potomac River and Rock Creek to the west, the Anacostia River to the south and east, and by Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue) to the north. LeDroit Park sits just north of Florida Avenue, in what was originally the rural Washington County, District of Columbia. The District also included the City of Georgetown, the City of Alexandria, and Alexandria County (now Arlington County, Virginia).

The map below, dating from 1792, was the first printed version of the L’Enfant Plan (as amended by Andrew Ellicott) for the City of Washington. Notice that its northern boundary coincides with what is now Florida Avenue. LeDroit Park now sits just to the west of what is marked as “Tiber Creek”. The creek, also called Goose Creek before the founding of the city, originally ran between First and Second Streets NW through Bloomingdale all the way to what is now Constitution Avenue NW, and westward toward the Washington Monument grounds, where it emptied into the Potomac River. Much of the creek is now buried in pipes beneath the city.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress

(We have a reliable method of identifying the future LeDroit Park on old maps of Washington: look for New Jersey Avenue NW, which runs diagonally to the northwest from the Capitol. Directly north of where it ends at the city’s border is where LeDroit Park would later be built.)

The capital city grew slowly over the coming decades with new residents, including government workers and Members of Congress, housed in newly constructed houses and boarding houses near the White House and Capitol, respectively. The difficulty in finding enough skilled labor to build a capital city required the leasing of slaves, who were instrumental in constructing many of the grand public buildings that stand today.

It would be a mistake to look at the map above and assume that all the new streets and canals were built together. In fact, the L’Enfant Plan was just that, a plan. The grand, spacious avenues required the clearing of trees and brush after a tedious survey to match the ground with the map.

In fact, by 1842 so much of the city was incomplete that a visiting Charles Dickens belittled Washington as a “city of magnificent intentions” marked by

spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.

Whereas the global financial markets of today allow developers to develop large tracts of land at once, 19th-century cities had to be built piecemeal with speculation limited to small projects. LeDroit Park was no different: only several houses and only a few streets were built at first with the rest to come later.

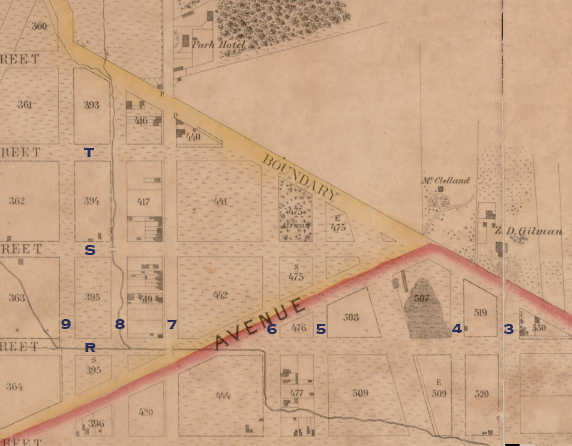

From 1856 to 1859, German cartographer Albert Boschke charted the District hoping to sell his maps to the U.S. Government. His 1859 map of the City of Washington (below) provided illustrative evidence supporting Charles Dickens’s sneer. Much of Washington, especially its northern reaches near what was to become LeDroit Park, sat undeveloped with only a few cleared streets.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

Download the full version of this map from the Library of Congress. To aid orientation, we have superimposed a few street names.

The only clear north-south street was Seventh Street, which connected the city with the rural county and stretched into Maryland (albeit under different names). At R Street— if one could call it a street— it crossed an open creek that ran through the right-of-way.

Seventh Street’s primacy as the main north-south thoroughfare actually contradicts the intention of the L’Enfant Plan, whose Baroque determination to provide a “reciprocity of sight“, plotted Eighth Street, not Seventh Street, as the more important axis. In fact to this day the right-of-way of Eighth Street is fifteen feet wider than those of Seventh and Ninth Streets, even though Eight carries only a fraction of the traffic burden that the parallel streets carry.

It is difficult to enforce one artistic vision on a democracy; the shifting of axes, from Eighth to Seventh, merely reflects the fact that cities are shaped by their inhabitants in ways the founders never anticipate. The future LeDroit Park was no different.

Next: Alfred Boschke maps the entire District and a future LeDroit Park resident prints it, only to have it seized at gunpoint.

Recent Comments