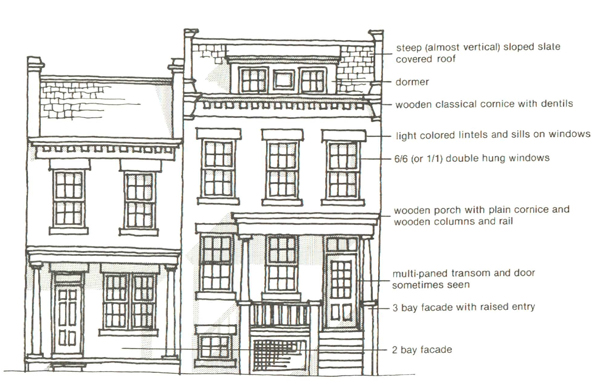

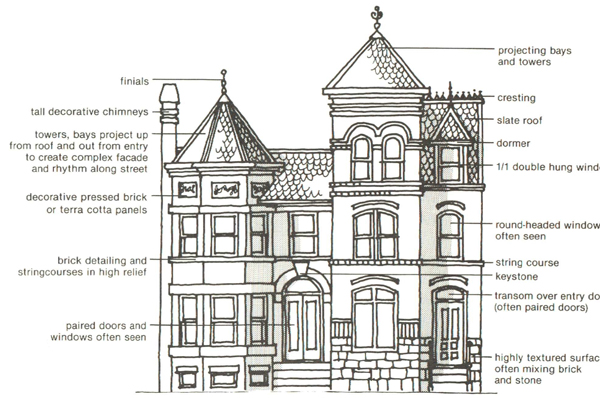

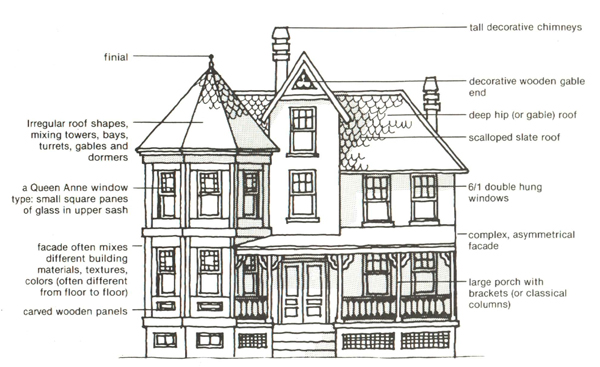

Can you identify LeDroit Park’s 12 distinct architectural styles?

The Washingtoniana Division of the M.L.K. Library contains a great collection of books on the history of Washington. Since all the material in the section is reference material, none of it can be checked out.

The kind librarians, however, permitted me to scan the entire book LeDroit Park Conserved, produced in 1979 for the DC government.

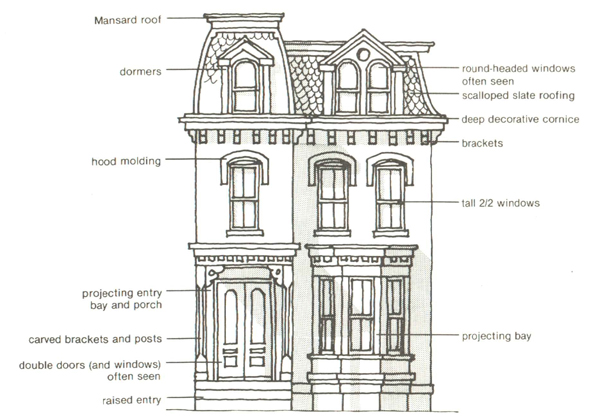

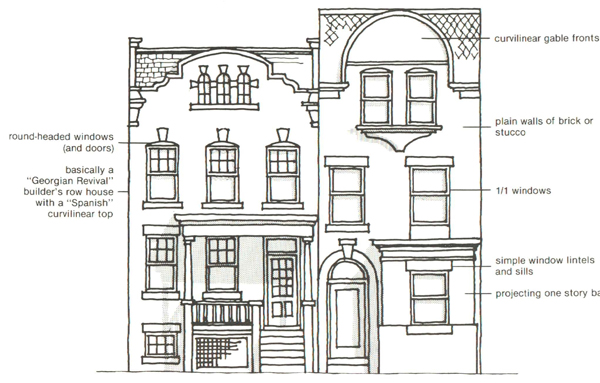

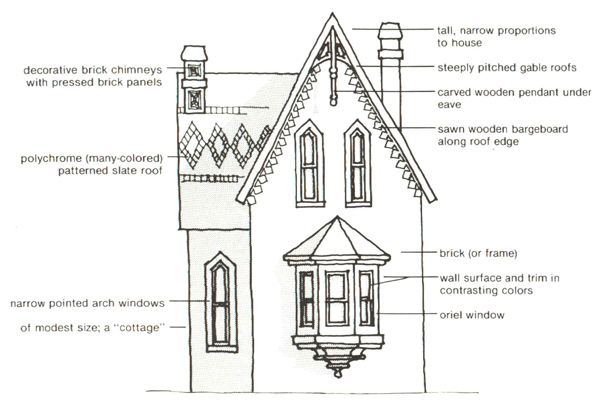

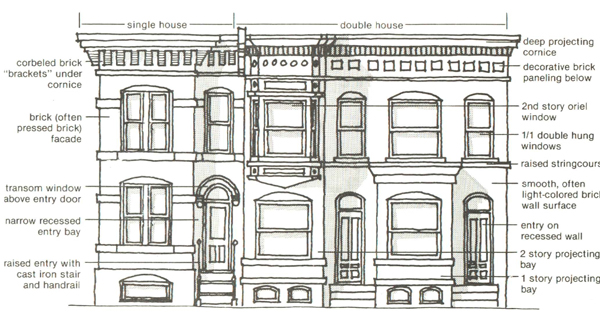

The book covers the historical development of the neighborhood, documents the different architectural styles, and offers suggestions to residents who wish to restore their properties with greatest historical accuracy.

Most surprising to me was the number of architectural styles represented in LeDroit Park. Let’s review:

View the entire book for all the details, photos, diagrams, and maps.

Just who was Ernest Everett Just?

An academic’s prestige is usually measured by the degree to which his peers admire his work. Any job where success depends on reputation is bound to be a difficult and political career. Howard biologist Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941), who lived at 412 T Street in LeDroit Park, faced a constant struggle for recognition for his groundbreaking work in biology in the early 20th century.

I occasionally give history tours of the neighborhood. My tour touches on two major themes: the neighborhood’s eclectic architecture and the prominent black Americans who lived in LeDroit Park. I had never heard of Just before moving to LeDroit Park, but in researching topics for my tour I came across a 1995 postage stamp commemorating him. This makes him the first of two LeDroit Park residents featured on postage stamps.

Two months ago, a neighbor who was a researcher at Howard University recommended Kenneth Manning‘s 1983 biography of Just. He assured me that the book, entitled Black Apollo of Science, detailed all the administrative problems at Howard that still exist to this day.

I picked up the book hoping to read historical accounts of LeDroit Park while Just lived in the neighborhood. Though there was very little about the neighborhood, the book provided interesting stories about Howard University’s administrative and financial troubles during the early 20th century.

The book was light on LeDroit Park and Washington because Just himself increasingly disliked teaching at Howard and the pervasive racism he faced living in the United States. In the 1920s, midway through his career, Just began to spend more time conducting research at research institutes in Berlin; Naples; and Roscoff, France. He deliberately avoided returning to the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where he felt he was socially isolated because of his race. Just saw Europe as an escape from racism he faced at home.

In Europe Just could finally attend the same operas he had seen advertised in Washington’s whites-only venues and he could travel and book hotels without worrying that his reservations would be rejected due to Jim Crow.

Whether Just was pursuing his PhD at the University of Chicago or conducing research in Massachusetts or Europe, his wife and children remained in LeDroit Park at 412 T Street. But as Just eventually grew apart from the United States, he also grew apart from his wife. Just took several lovers in Europe during his research stints and he eventual filed for divorce from his wife Ethel in the late ’30s. This was a formality, though, as their love had died many years ago.

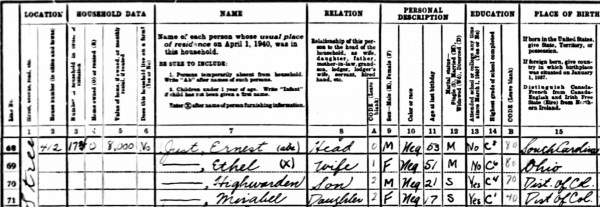

Though Just was in France at the time of the 1940 census, the census ledger lists him as the absent head of household at 412 T Street.

The Just family stood out for its educational attainment. Notice that in column 14, Just is listed as having completed eight years of college, an outstanding accomplishment even by today’s standards. His wife had finished six years of college, his son four, and his daughter Maribel, aged 17, was in her first year of college.

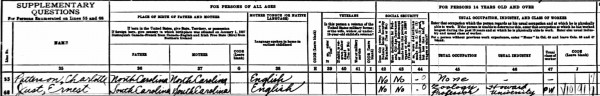

Out of pure luck, Just was listed on line 68, which was one of two lines per page that the Census Bureau selected for supplmentary questions.

Here Just stands out again. Though most LeDroit residents were listed as maids, porters, or laborers, Just’s profession is listed as “Zoology professor” at Howard University.

Just’s life was not easy. He grew up in poverty and his father died when Just was a child. Just’s mother was a teacher who valued his education dearly and she sent him as a teenager to a boarding school in New Hampshire. During his time at boarding school, his mother died, leaving Just orphaned but independent.

After boarding school, he proceeded to Dartmouth to study classics and biology, the field to which he devoted his entire career. Since few universities at the time would hire black researchers or professors, Just took a position at Howard University and in 1912 became the head of Howard’s Department of Zoology.

The Howard position was Just’s main source of income for the rest of his life and he used it, along with a few private grants, to fund his research in Massachusetts and Europe. Though Just kept his position at Howard until his death, he spent many semesters and summers studying marine biology far away from Washington. Howard, it seems, was only a source of income for Just, as he frequently battled with the university’s administration for more equipment, more funding, and more research time.

Howard’s presidents, especially Mordecai Johnson, demanded that Just focus less on research and more on teaching and building a graduate zoology program.

Johnson wasn’t the only person pressuring Just. White philanthropists who wanted to raise academic achievement and living standards of American blacks funded Just’s work with the goal that he would train aspiring black scientists and doctors. Their hope was that Just would train black biology students so they could study medicine and return to the rural south where white doctors would not treat black patients.

Just, however, wanted philanthropic funding to support his biological research efforts, not his teaching efforts. Just preferred research and appeared far more interested in advancing the human understanding of cell biology.

Old letters Manning uncovered reveal that Just held a low opinion of Howard undergraduates during his tenure. Just thought teaching biology to them was a waste of time and would distract him from important research.

To teach or to research? This is an old academic controversy. Many professors prefer to conduct research because they find it more intellectually satisfying and because it builds their careers, expertise, and reputations. At universities that rely heavily on tuition fees for their income, administrators realize that teaching is an important source of income.

For Just, the written correspondence between him and various philanthropies shows that because he was black, he was expected to carry the herculean task of advancing both the human understanding of biology and the welfare of his race— a burden his white benefactors did not place on white scientists. These expectations, though well intentioned, continually hindered Just’s career as his appeals for research grants rarely bore fruit. Various foundations and Howard administrators urged Just to spend more effort building a biology program and producing trained biologists.

Just found a warmer reception in Germany, Italy, and France, where scientists were more eager to collaborate with him and build on his work. While in Europe, Just dated several women. He even established residence in Latvia briefly so he could quickly file for divorce from his wife in Washington. He eventually decided to mary his German mistress and start a life in Europe, even if it meant resigning his post at Howard and living in penury in Europe.

Failing to win grants, though, Just held onto his Howard position as his sole source of income. Just’s time in Europe was productive. He published his most renowned works on cell biology and cell fertilization during this self-exile.

His new-found haven across the Atlantic didn’t remain peaceful for long. Though he had tried to escape racism in the United States, Nazi violence had made Berlin inhospitable. In Italy, Just’s appeals to Mussolini for research funding went nowhere and Italian biology conferences became fascist propaganda events.

Just’s final European post in France came under Nazi control and Just was ordered to leave. The advancement of fascism eventually made this European exile untenable. Sadly, everywhere Just went, some virulent -ism— racism, fascism, Nazism— eventually caught up with him.

Just returned to the United States with his new wife and newborn child. His new wife and child settled in New Jersey, but Just had to return to work for pay at Howard. Suffering from pancreatic cancer, Just stayed with his sister Inez at 1853 3rd Street, here in LeDroit Park. His health was in rapid decline and in October 1941 Just died.

Despite having overturned a ruling theory of cell fertilization, Just never fully received the professional recognition he desired and deserved. He was always tied to Howard, even though he wanted desperately to leave to focus solely on research. Howard tied him to Washington, a city whose segregation degraded him. Washington also tied him to a wife he no longer loved.

Manning’s book is very well researched and combs through many of Just’s letters to colleagues, mentors, friends, and lovers. It tells a fascinating account of race relations in America, the history of biology research, and one man’s unhappy task facing down all these problems.

Manning was able to weave these threads of science, race, academia, and Just’s personal life into a unified and compelling work accessible to the general reader. Happy endings are the work of fiction writers; Just’s story is more poignant because it recounts a life marked by great successes and great disappointments.

Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just

Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just

By Kenneth Manning

1983, Oxford University Press. 330 pages.

[Amazon] [DC Public Library]

Will Florida Avenue become the next U Street?

When perusing the excellent interactive DC zoning map, one thing stands out around LeDroit Park: all the properties fronting Florida Avenue are zoned to permit both residential and commercial uses. Even the rowhouses on the LeDroit side of Florida Avenue can be turned into restaurants, offices, or shops without any need for special zoning approval.*

We mention this not to alarm anyone, but to educate residents about the influence of zoning ordinances. Zoning is the invisible geography that quietly shapes the use and form of the built environment.

The north-side rowhouses on the 400, 500, and 600 blocks of Florida Avenue were clearly built as homes. About 100 years ago, many of these rowhouses hosted the offices of Washington’s prominent black doctors.

Neighborhoods change and businesses move and nearly all the rowhouses on our stretch of Florida Avenue reverted to their original uses as residences. Even the notable Harrison’s Cafe at 455 Florida Avenue is a residence with much of its former retail bay window bricked in.

A few businesses still dot Florida Avenue. While Shaw’s Tavern and Bistro Bohem are reviving the corner of Florida Avenue and 6th Street, they occupy buildings that are clearly commercial in form. Thai X-ing, however, has been located for several years in and old rowhouse at 515 Florida Avenue NW. Though it looks like an abberation, Thai X-ing may just be ahead of its time.

The properties fronting Florida Avenue are zoned C-2-A, which permits as a matter of right,

office employment centers, shopping centers, medium-bulk mixed use centers, and housing to a maximum lot occupancy of 60% for residential use and 100% for all other uses, a maximum FAR of 2.5 for residential use and 1.5 FAR for other permitted uses, and a maximum height of fifty (50) feet. Rear yard requirements are fifteen (15) feet; one family detached dwellings and one family semi-detached dwellings side yard requirements are eight (8) feet.

There is no need to worry about an old rowhhouse being torn down and turned into office blocks. First, the houses along the LeDroit Park side of Florida Avenue are within the historic district. Historic preservation laws prevent drastic alterations, especially alterations to such an cohesive section of architecture.

Second, the C-2-A zone is a low-density zone, permitting a floor-area ratio (FAR) of only 1.5 for non-residential uses. Most of the existing rowhouses already exceed 1.5 FAR since they were built before the current zoning code.

The opening and success of Shaw’s Tavern and Bistro Bohem demonstrate business success along our stretch of Florida Avenue. There is clearly a demand for commercial activity near LeDroit Park and we were happy to spend Sunday afternoon revisiting Bistro Bohem. Whether this demand translates into rowhouse conversions into restaurants and bars remains to be seen. Even still, don’t be surprised if Thai X-ing gets a few restaurant, pub, cafe, or boutique neighbors in the coming years.

* Though one may open a restaurant without special approval in a commercial zone, a restaurateur must still follow the usual process for obtaining a license to serve alcohol.

7th & Florida in ’68, ’88, and today

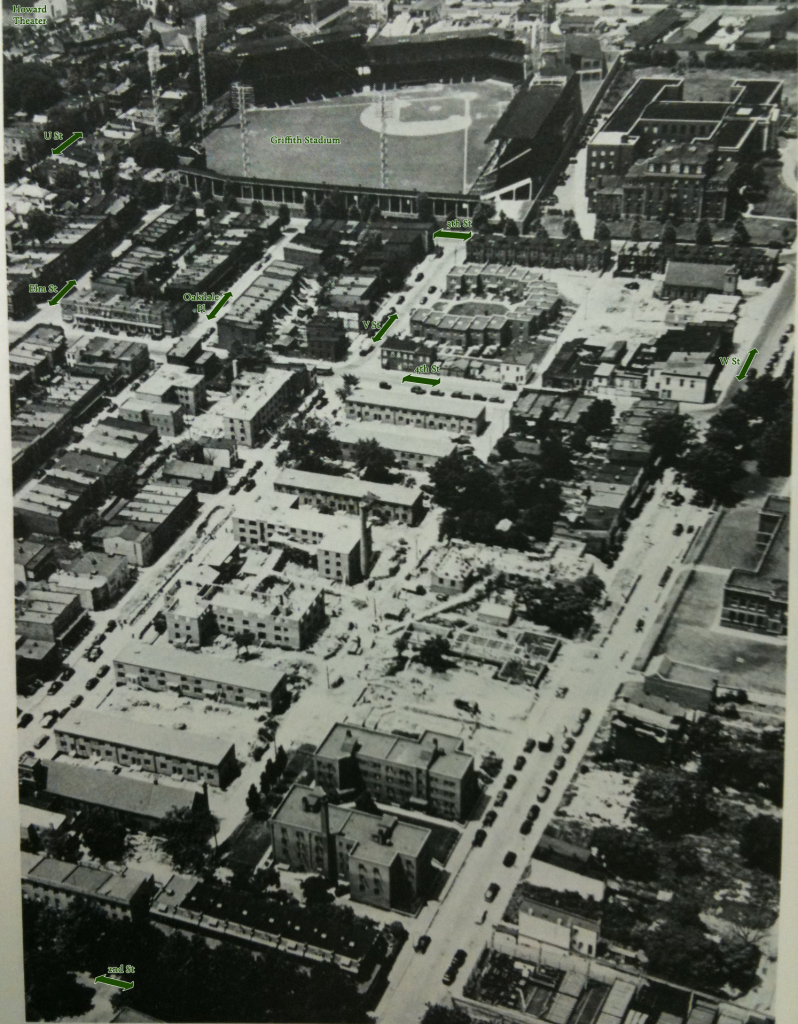

What happened to all the historic buildings at 7th Street, Florida Avenue, and Georgia Avenue? We all recognize the CVS and its adjacent parking lot. As we reported before, the adjacent grassy field is slated for a residential development by JBG, one of the region’s largest development companies.

But how did the CVS, the parking lot, and the grassy field get there in the first place? They are the consequence of the 1968 riots and of the construction of the Green Line tunnels.

The riots of April 1968 destroyed many of the buildings along 7th Street. A few months ago we came across this photo in a Congressional report published in the wake of the riots. The west side of 7th Street from T Street to Florida Avenue was obliterated:

Decades later, the intersection sat at an elbow in the proposed Green Line tunnel. The subway line curves from 7th Street to Florida Avenue and then to U Street. Much of the line was constructed using the cut-and-cover method, which requires razing buildings, digging a trench, building a concrete box in the trench, and covering it back over.

Subway tunnels typically run under existing streets, but sharp changes in direction require cutting corners and thus the creation of tunnels where buildings often stand.

A 1988 photograph shows the construction of the Green Line tunnels, which pass under the CVS and adjacent lots.

What the riots didn’t destroy, the Green Line took care of.

Neighborhood history trail nearly complete

LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale history buffs need to mark their calendars for Thursday night. The LeDroit Park-Bloomingdale Heritage Trail Working Group will meet to go over updates to the pending bi-neighborhood heritage trail.

LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale history buffs need to mark their calendars for Thursday night. The LeDroit Park-Bloomingdale Heritage Trail Working Group will meet to go over updates to the pending bi-neighborhood heritage trail.

You’ve seen these heritage trails elsewhere in Washington. The signs feature historical photographs and explanations of the areas’ historical significance.

At the last meeting we attended, we heard from residents who lived in the neighborhood that stood where the Gage-Eckington School was later built, neighbors who had to walk several extra blocks to school because Washington ran a segregated school system, and neighbors who remember seeing Eleanor Roosevelt visiting what is now Slowe Hall at 3rd and U Streets.

These are the oral histories that Cultural Tourism, which organizes these trails, documents for the historical record and includes in the signs. So much of Washington’s history, nay human history, is committed to memory that if we don’t record it, it risks being lost.

The trail, which is put together by Cultural Tourism DC, is close to completion, but the next few meetings are critical in determining final details and extra stories that may be incorporated. Even if you don’t have stories or original research to contribute, attending the meeting solely to listen will be worthwhile.

Thursday, April 19 at 7 pm

St. George’s Church (basement)

2nd & U Streets NW

44 year ago today, Washington burned

A neighbor pointed us to this poignant video footage of the riots that occurred 44 years ago here in Washington after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

Contrary to popular belief, suburban flight and urban disinvestment were already well-underway by 1968. The destruction that occurred in American cities that year was not the cause of urban decay; it merely accelerated a pre-existing, post-war urban decline. Most middle-class Americans, regardless of race, do not want to live or shop in a war zone, after all. Thus DC’s commercial districts quickly declined.

The riots that year were a mixed result: they meaningfully displayed frustration at systematized racism in American society, but they also destroyed the essential businesses in DC’s majority-black neighborhoods.

The sociology of the matter is controversial, but it’s important we review accounts of the history just to know what happened.

Look carefully at video and you’ll recognize 7th Street in Shaw, U Street, and 14th Street. Washington was never the same after April 1968.

Neighbors reminisce about the Howard Theatre

In preparation for the Monday’s grand (re)opening of the Howard Theatre, the Post ran a story about the theater’s past and how the Shaw and LeDroit Park have changed over the decades since the theater’s heyday.

In preparation for the Monday’s grand (re)opening of the Howard Theatre, the Post ran a story about the theater’s past and how the Shaw and LeDroit Park have changed over the decades since the theater’s heyday.

The article also describes the histories of some long-time local businesses, including the Hall Brothers Funeral Home, the HJM Variety Shop, and Gregg’s Barber Shop.

A neighbor we know who studies local history likes to ask long-time residents if they feel the city has lost anything with the influx of residents, wealth, and investment over the past 15 years. Inevitably, the answer is yes and the answers differ to some degree.

The Post article is striking in that the residents who remember the theater in its golden age don’t expect its current incarnation to live up to the excitement of its younger self.

For those Washingtonians, the Howard’s rebirth stirs a mix of curiosity and excitement for what is new, and nostalgia and melancholy for what has been lost.

“It looks like a mausoleum to me,” said Juan Rosebar, 61, eyeing the theater on a recent afternoon, as workers laid cobblestones on the street outside.

As a kid, Rosebar watched the stars migrate from the Howard to Cecilia’s Stage Door, a bar a few yards away where they’d mix with their fans and drink post-performance cocktails. Cecilia’s closed long ago, as did Jimmy’s Golden Cue, the pool hall across the street where Rosebar learned to hustle. All that’s left is Jimmy’s rusted sign, the letters barely legible.

“You can’t turn the clock back,” Rosebar said. “You won’t get the scene; you won’t get the flamboyance.”

Another resident, Frank Love, concurs:

“It’s all changed around here,” said Love, 77, shaving a customer’s sideburns and listing the names of a half dozen long-gone barbershops. He can’t wait for the Howard’s reopening and the chance to step inside the place where he went to see Jackie Wilson with his future wife, Pearl Love.

He knows the theater can’t be what it was, but he’s okay with that. “That was then, and this is now,” he said. “You can’t look for it to be the same.”

You can tell from the posts on this blog that history fascinates us. However, the study of history is part real and part imagined. Though buildings can be preserved and restored, the people and societies that made them relevant cannot. The Howard will reopen on Monday and it will serve as a lively venue for a diverse array of national acts, but its cultural relevance may never again match its storied past.

Historian describes Mickey Mantle’s LeDroit Park home run record

On April 17, 1953, Mickey Mantle hit one of the longest home runs in baseball history at Griffith Stadium, which stood where Howard University Hospital stands today. The ball landed in LeDroit Park and was alleged to have traveled the remarkable distance of 565 feet.

Sports historian Jane Leavey investigated the so-called “tape measure home run” in her 2010 book The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood. She appeared on NPR’s Talk of the Nation yesterday to discuss that record-setting home run that landed in LeDroit Park and she described her efforts to verify distance claim.

The 1940 Census reveals a full profile of LeDroit Park

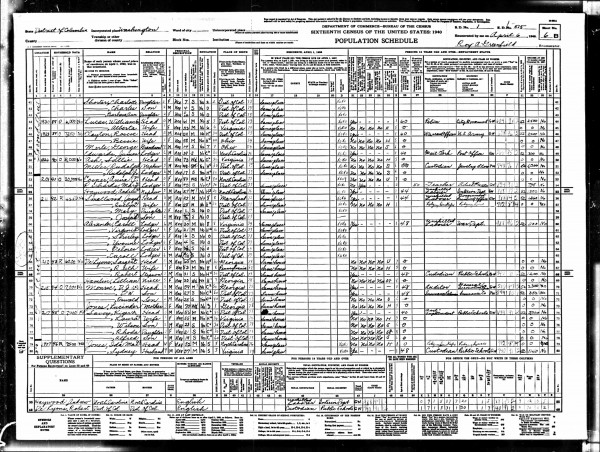

U.S. Census records are kept confidential for 72 years, meaning that the 1940 Census went public yesterday. Whereas previous census ledgers were difficult to find online for free, the U.S. Archives released the full 1940 Census online. We have started perusing the pages to look for famous figures and interesting patterns in LeDroit Park, which is covered by enumeration districts 1-514 through 1-516.

A few things stand out. First, nearly the entire population of LeDroit Park in 1940 was black, illustrating the sharp racial segregation at the time. Second, nearly every house was packed with residents and many residents took on lodgers. Our house, a modest two-bedroom built in 1907, housed 13 people!

* * *

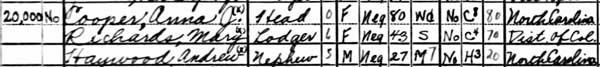

We will publish some interesting records as we find them, but let’s start off with the listing for Anna J. Cooper (née Haywood), her lodger, and her nephew, who lived at 201 T Street (pictured below). The Cooper household is listed as entries 53 – 55 in the ledger at the top of this post.

Cooper was the principal of the M Street High School, she was an author, a feminist, and a teacher. The census only collects unambiguous personal statistics, so there is actually a longer story behind every column entry.

Cooper was the principal of the M Street High School, she was an author, a feminist, and a teacher. The census only collects unambiguous personal statistics, so there is actually a longer story behind every column entry.

The first column in the snippet above states the value of her home as $20,000, a high sum compared to other LeDroit Park homes.

The 11th column lists “C8”, meaning that she received eight years of a college education. What the record doesn’t state is that she received a PhD from the Sorbonne in 1924, making her among the first black American women to receive a doctorate.

The 8th column states her age as 80 (she was actually 81) and the 13th column simply states that she was born in North Carolina. What the record doesn’t state is that she was born in North Carolina in 1858 into slavery.

The rest of the record not pictured in the above snippet states that by 1940 she was unable to work, though in reality she was likely still running a small night school.

She died in 1964 at the age of 105. The circle at 3rd and T Streets is named in her honor, she is featured on a postage stamp and on pages 26 and 27 of the U.S. passport.

Duke Ellington immortalized in stainless steel

The Howard Theatre is nearly complete. You may have noticed that the sidewalk on the north side of T Street is now open, giving residents a close-up view of the new façade. More importantly, the plaza at T Street and Florida Avenue is now open and the new sculpture of Duke Ellington stands prominently at the vegetated plaza. The sculpture depicts Ellington seated on a treble clef while playing a piano keyboard.

The most delightful feature of the sculpture is the energy it portrays. As Ellington plays, the keys appear to fly off the keyboard and into the sky behind him, signifying a magical quality to his music.

Duke Ellington grew up in Washington and even lived on Elm Street in LeDroit Park for a year. He played at the Howard Theatre and frequently visited the adjacent Frank Holliday’s pool hall, most recently known as Cafe Mawonaj.

The hall was a popular gathering spot for Howard scholars, jazz musicians, and city laborers alike. Duke Ellington captured the scene at the pool hall:

Guys from all walks of life seemed to converge there: school kids over and under sixteen; college students and graduates, some starting out in law and medicine and science; and lots of Pullman porters and dining-car waiters.

And now Ellington’s statue sits on the same storied block.

Recent Comments